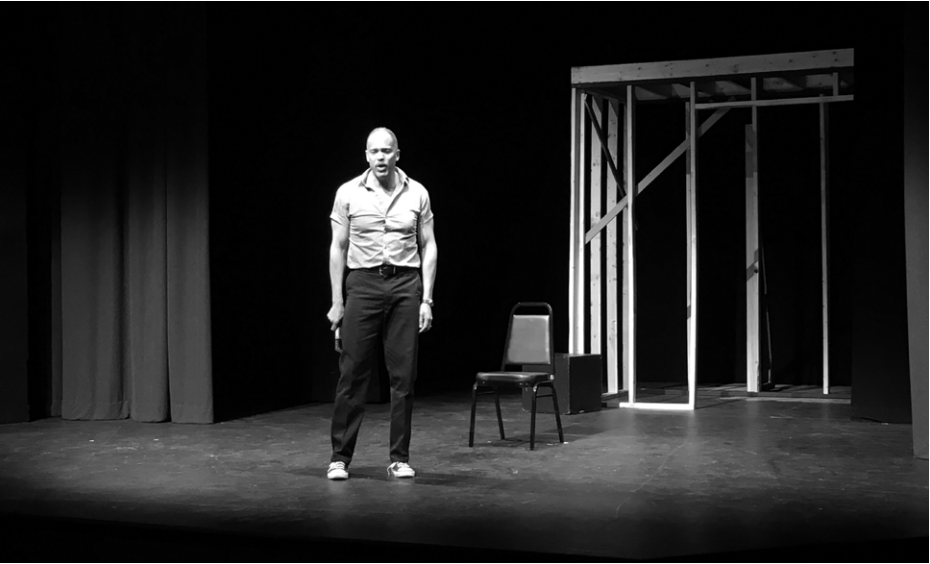

Photo by Saee Chitale ’22

Keith Hamilton Cobb onstage in his one-man show “American Moor.”

BY MIRANDA WHEELER ’19

Award-winning actor and playwright Keith Hamilton Cobb has accumulated a variety of impressive credits over the course of his screen and stage career, but none quite like “American Moor.” The self-written and largely self-performed play explores Cobb’s relationship as a black man in America to Shakespeare’s tragic protagonist Othello. “American Moor” is officially on the road, visiting a variety of colleges and theaters throughout the United States and abroad, including Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre in London. The production was in residence at the Rooke Theatre from Nov. 3-11, and included performances, post-show talk-backs and a series of speaking events across the Five Colleges.

Directed by Kim Weild, “American Moor” follows an unnamed black actor, the fictionalized version of Cobb, as he auditions for the part of Othello. Embedded within the audience is an unnamed director, played by Josh Tyson, who calls out direction to Cobb’s character, stereotyping and overstepping as he fails to grasp the significance of the character, its history and its implications.

The production is without a set designer, instead selectively borrowing from what exists in the spaces they inhabit with each residency. During a Sunday matinee talk-back, Weild explained that the only set piece, a house-like structure made of wooden beams, that became central to the show while in residence, is “actually a piece of ‘The House of Bernarda Alba,’” referencing Rooke’s Dec. 9-11 show from playwright Federico Garcia Lorca.

“American Moor” opens with Cobb onstage from the moment doors open and the audience trickles in, already in character as he silently rehearses for an “Othello” audition. The play begins with his description of what it means to be an actor and his introduction to the work as an aside before the director interrupts, asking him to prepare for the audition. From then on, the work exists between two worlds: what happens inside Cobb’s head, performed as extended addresses to the audience, revealing what he resists saying in polite company, and what happens live in the audition room. This construct alters time and reality, relying on lighting design to indicate the shift between thoughts and words, a theatricalized exploration of what Cobb described as “code switching” and “self-editing.”

Cobb’s character compares one of Othello’s earliest scenes — where he stands before a group of senators, forced to defend his marriage and his position in society — to the experience of performing in the audition space, reflecting on his many different understandings of “Othello” during different periods of his life. Cobb’s character endures assumptions and misunderstandings until he cannot any longer; he finally confronts the director and invites him to engage in a conversation. “Watch and listen and you might learn something […] Meet me here in this sacred space with half the courage of Desdemona,” pleads Cobb’s character. After a gutting silence, the director simply responds, “Thank you for coming in.”

The 90-minute production, which takes place during the course of a real-time five minutes in the audition room, is a mixture of comedy, conflict and tragedy, reflecting on a decades-long acting career that began with performance training and eventually led to a discovery of and devotion to Shakespeare.

For Cobb, one of the most important products of the production is the conversations facilitated after. He told the Hampshire Gazette, “[Audience members are] afraid that the first thing out of their mouth, they’ll be indicted, so they don’t ask questions […] [“American Moor”] answers the questions that they’re not asking so they can just sit there and be part of the journey.” In the show, his character puts words to this phenomenon when speaking to Tyson’s director: “I am [accusing you] of not knowing what you couldn’t possibly know and [asking you] to admit you don’t know it.”

Although Mount Holyoke’s rendition of the production saw Tyson in the audience, it is not always that way. According to Weild, the choice emerged from a practical necessity: the Rooke Theatre is not presently equipped with a god mic, which is used to play sound over a theater’s PA system. Tyson’s director is usually a faceless voice from the speakers, a manifested emblem of “this omnipresent voice [Cobb’s character] has heard all his life.” The voice of the director blends into a series of alltoo-familiar encounters with misguided and problematic approaches to “Othello.” Cobb’s character credits these failings in part to the commodification of entertainment and the rushed assembly-line approach to too-brief rehearsals and inadequate training at MFA programs. The director’s sourceless, omnipresent voice embodies another important theme of the play: the relationship between race and American theater. “American Moor” heartbreakingly explores the result of the hyper-scrutinization and judgment Cobb’s character (and Cobb himself) have been subjected to, both as an actor and as a black man in America. His character explains to the director, “I can never just be me, and you can never just be you.”

During his residence at Mount Holyoke, Cobb visited Noah Tuleja’s “Stage and Screen Violence” class and Heidi Holder’s “Introduction to Theatre and Histories of Performance I” seminars among others, where he led conversations on the course material as it related to his education at NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts and his long film and television career. Events throughout the rest of his residency included four performances of “American Moor” and a Gamble Auditorium panel featuring Cobb and artist-in-exhibition Curlee Raven Holton. Cobb and his colleagues also gave two Rand Theatre guest lectures: “Shakespeare, Race, and America – not necessarily in that order” and “Othello Was My Grandfather: Shakespeare in the African Diaspora,” at UMass Amherst featuring Barnard College professor Kim F. Hall.