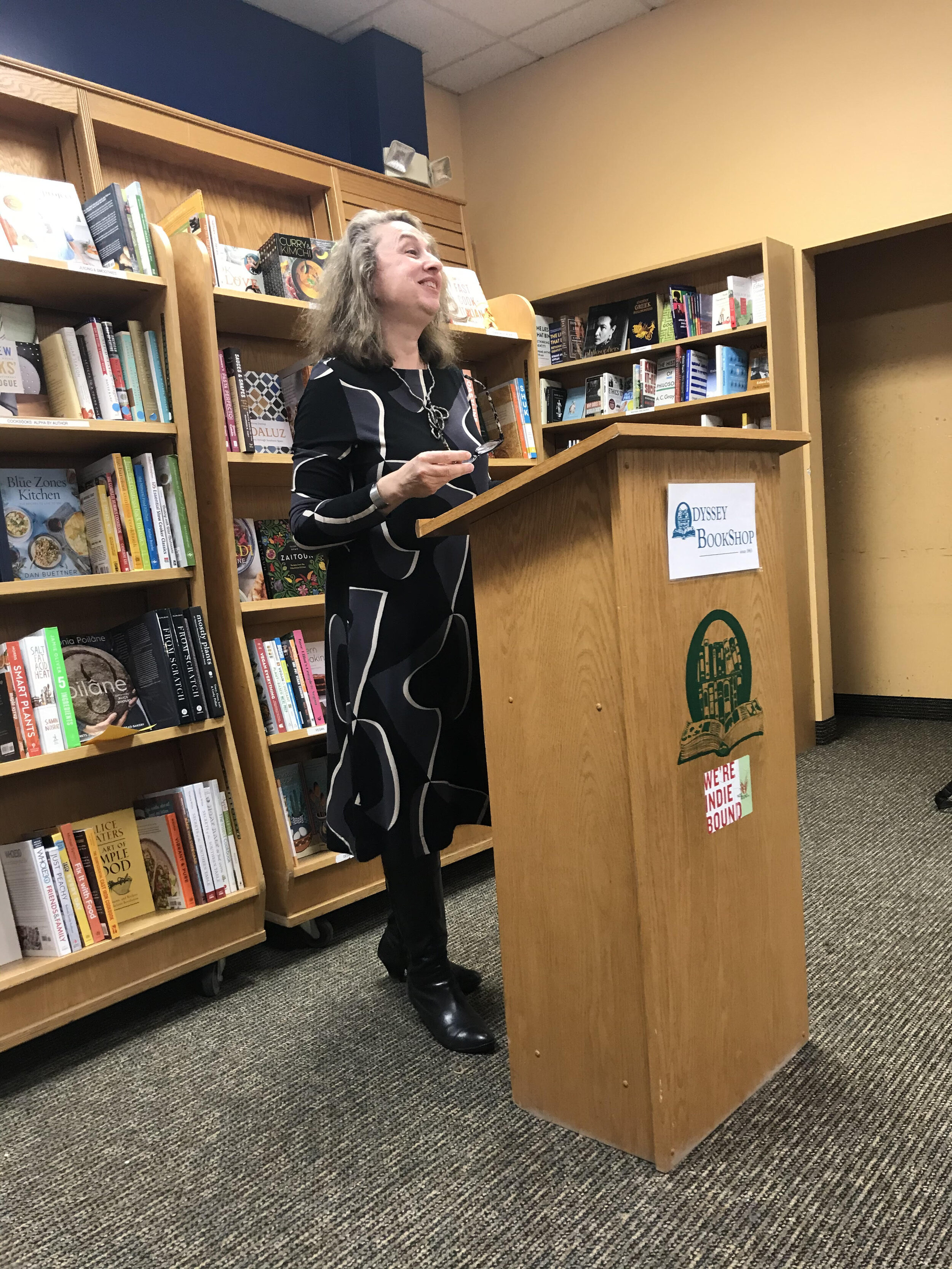

Photo by Deanna Kalian ’20

Elizabeth Young reads from her “eccentric” new book, “Pet Projects.”

On Thursday, Feb. 27, students, community members and faculty ambled into The Odyssey Bookshop for Professor Elizabeth Young’s reading of her new book, “Pet Projects: Animal Fiction and Taxidermy in the Nineteenth-Century Archive.” On a small table were drinks and refreshments shaped like animals.

Professors from the English, film and critical social thought departments attended.

Elizabeth Young is the Carl M. and Elsie A. Small Professor of English and the current department chair. Young opened her reading by thanking English and film faculty and the Mount Holyoke Art Museum, noting that she used three images from its collection in the book. She thanked James Girt, former instructional technologist at Library, Information and Technology Services (LITS), who took photos for the project. Young also expressed gratitude for her students. Young called “Pet Projects” an “eccentric” book with three subsections. It explores animal representations in the 19th century, exposes the process of scholarly investigation and is, at heart, a personal project. In the book, Young considers the politics and aesthetics of animal representations, asserting that abolitionists also fought for animal rights.

The second purpose of the book is to “highlight the process of scholarly investigation.” She accomplished this through interdisciplinary work, often with new-to-her academic fields. “Pet Projects” includes literary criticism, gender studies, film studies, American and Canadian studies, critical race studies, animal studies, cultural history and psychoanalysis. Young also delved into the “non-animal topics” of death, mourn- ing, race, slavery, ventriloquism and femininity.

In addition, Young wanted to expose the emotions involved in a scholarly project. She wrote the book in first-person voice: a “stylized version of [her]self.”

She said that she chose the first-person self-reflexive voice “to make visible and track scholarly movements so often effaced in scholarly writing.” Young also employed wordplay and puns to focus on stylistic techniques; as she remarked, “I’m a huge fan of the semicolon.”

Finally, “Pet Projects” was a personal project, a memoir Young “never thought [she] would do.”

“I wanted to honor rather than shirk from the idea of a pet project,” she continued.

Young admitted that the project was “risky,” and she embarked upon it “with great trepidation,” pointing out the taboo against women writing about pets, which is seen as too “sentimental.” She also mentioned that the narrowness and eccentricity of the book’s topic, as well as its risk of being too “cute,” were hazards of writing such a work of creative nonfiction.

Reading from the introduction, Young again called her first paragraph “risky” due to its unconventional subject matter and style of writing. The book begins in March 2008 during Mount Holyoke’s spring break, as she walked her golden retriever, Frankie, to his annual veterinary checkup. The doctor found a lump in his abdomen, which led to a discovery of hemorrhaging cancer. Young rushed Frankie to Tufts’ Cummings Veterinary Medical Center where the surgeons managed to remove most of Frankie’s cancer.

Young discovered that Cummings Veterinary Medical Center was built on the site of the former Grafton State Hospital, a farm colony for “insane patients,” which sparked her interest. She remarked that Mount Holyoke Female Seminary was built in the style of an asylum. “All roads in New England lead to a 19th-century insane asylum,” she quipped.

This experience reminded her of Canadian writer Margaret Saunders’ 1893 novel, “Beautiful Joe: an Autobiography,” written for the American Humane Education Society Prize Competition. Written in the voice of a dog, “Beautiful Joe” reminded readers of “Black Beauty,” which came out only a few years earlier and was narrated from the horse’s perspective.

“As I watch my dog in pain, I wish for him to have his own voice,” Young read. Young chose to focus on two themes: voice and skin, through the workings of two unusual rhetorical forms. “First-dog voice” is an impossibility because dogs do not speak, and “literary taxidermy,” as Young wrote, “combines literature with an activity that requires not human words but animal skins.”

According to her, these two methodologies provided Saunders and other writers “imaginative avenues for revivifying the dead and remediating loss.”

Young concluded her introduction boldly. After cataloging the aforementioned risks of such a project, she wrote, “I will take all of these risks anyway.”

She then read from the third chapter, “Literary Taxider- my.” It began with her visit to the Natural History Museum at Tring in England and ended with a discussion of taxidermy’s popularity today. One hundred thousand people in the U.S. alone participate in taxidermy. “I have an ambivalent attitude towards taxidermy: fascination and horror,” Young said. She explained that this attitude resulted from the paradox of taxidermy’s aesthetics and ethics. According to Young, “the viewer cannot avoid the visceral violence of taxidermy.”

She transitioned from the study of dogs to birds, citing Alfred Hitchcock films “Psycho” and “The Birds.” In “Psycho,” Norman favors stuffed birds over other taxidermied animals because of their “passivity.” The bird attacks in “The Birds” “reverse the taxidermist’s violence against them,” according to Young.

Young asserted that Hitchcock pursued avian taxidermy as a form of male violence. This contrasts with Saunders’ avian biography, “My Pets: Real Happenings in My Aviary,” a collection of essays about the everyday life of pets, as were recorded in the author’s diary.

Young visited the Booth Museum of Natural History, which houses a large collection of taxidermied birds. The museum displayed the English eccentric version of taxidermy, hinging upon exclusively male sportsmanship, she said. Edward Booth himself — the museum’s founder — recorded the names of his dogs in his diaries, but not his wife’s name. At the museum, Young began to think about Frankie; golden retrievers were bred to hunt birds.

“The museum resembles ... a large bird prison,” Young wrote. “Still I look, bird-doggedly, at the mounted animals, and still I smile, neither feather-headed or bird-brained, at taxidermy’s wonders.”