Image courtesy of Kylie Gellatly FP ‘22

By Declan Langton ’22

Managing Editor of Content

Kylie Gellatly FP ’22 isn’t one for a backstory or explanation. “I’ve never even attempted to do this,” she said in regard to summarizing over a decade of time that led her to Mount Holyoke and the publication of her first book. For Gellatly, this is best summarized through her art and creative process. When speaking at the FP Monologues on March 23, instead of talking about her journey to Mount Holyoke or a key event in her life that led her to who she is today, Gellatly shared a handful of poems, all to be published July 16 in her book “The Fever Poems.”

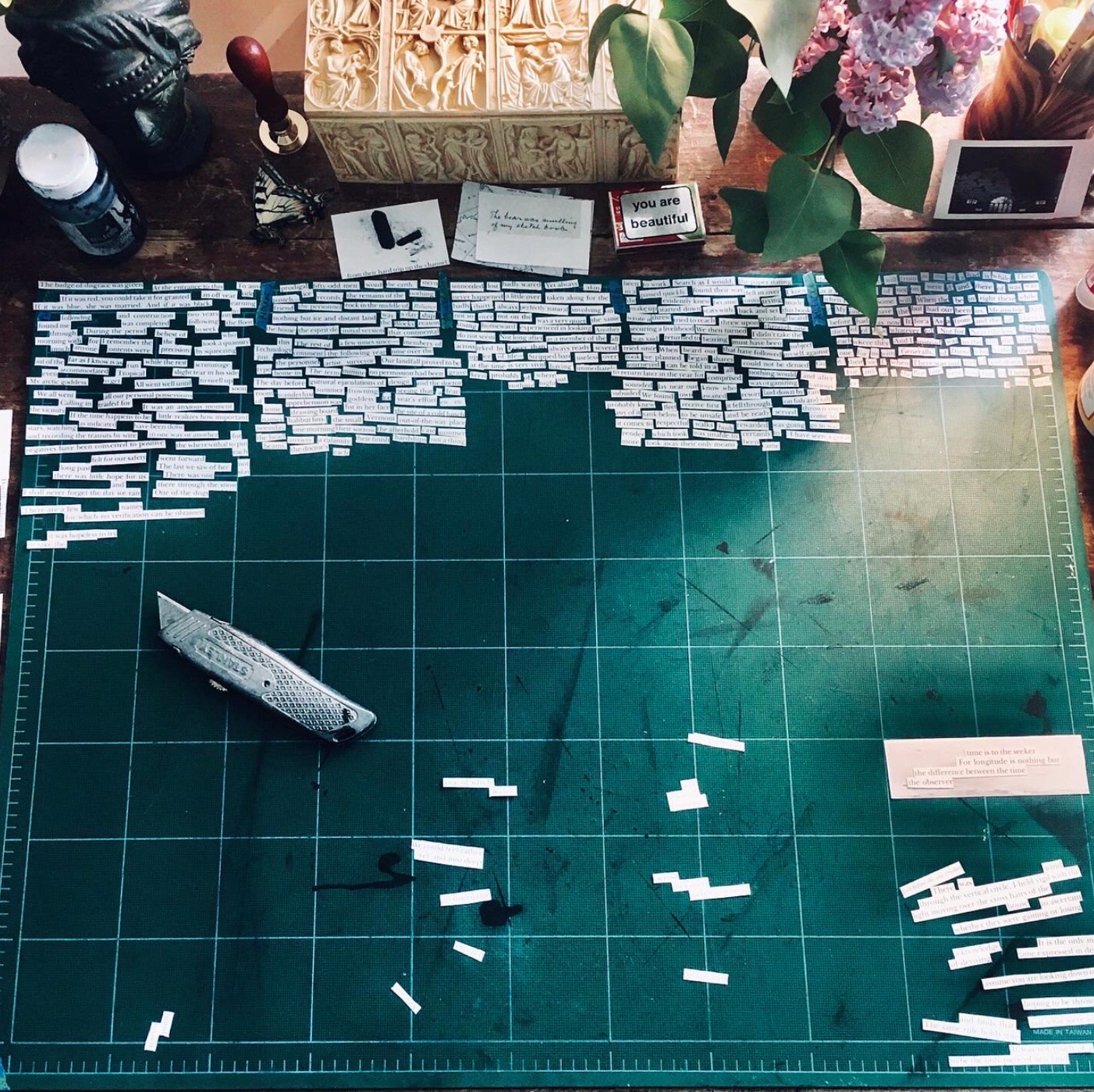

“The Fever Poems,” a volume of 38 poems in three parts, is the poet’s first collection. Gellatly’s collection is made entirely of found poetry, with words sourced from the book “The Arctic Diary of Russell Williams Porter.” The diary is a recounting of Porter’s explorations within the Arctic Circle. Gellatly spent the spring and summer of 2020 cutting up the book and rearranging the words and drawings around one another to create an entirely different story. Despite being made from someone else’s words, “The Fever Poems” is entirely Gellatly’s creation: a combination of hard work and creative labor to meld Porter’s adventures into an abstract recounting of the last year.

Gellatly is originally from Connecticut, but in the last 10 years has moved up and down the East Coast. After graduating high school, she moved to Richmond, Virginia, where she worked as a chef and butcher while playing music.

“I was in a few bands,” she said. “A band for my own music [in which] I was the guitar player and songwriter and singer. And then I did backup vocals and lead guitar in a different band, then played bass and backup vocals in another one,” she explained. It was during this time that Gellatly met some of the modern legends of the Richmond music scene, including indie rocker Lucy Dacus, who was the opener for Gellatly’s band’s final show.

Music, though, wasn’t the creative outlet Gellatly wanted.

“My parents are both artists, and so I was raised under the notion that’s like, ‘You have to figure out a way to speak your language and create your own language,’” she said. “I tried a number of different things. I started as a dancer, I did painting, I did photography. Music felt like it was maybe what was going to click,” she said. But, “It didn’t click.”

Around the time she started becoming “jaded about music,” Gellatly realized she had never read a book by a woman. “I just started reading books only by women for like the next two years. And, you know, poetry is a place where women really have a voice and do some really badass things,” Gellatly said.

The freedom of poetry enticed Gellatly. “I also didn’t have a good education. So poetry, with all the ways of, like, breaking rules … and the experimentation and how visual it is, too, felt like a really natural place for me to kind of land,” she explained.

This took Gellatly out of Virginia and up to Vermont, where she became involved in the Vermont Studio Center. “I moved there because I was like, ‘I don’t want to be a cook, I want to be a writer.’ And ‘I don’t want to play in bands, I hate music,’” she said. Her three-year art residency in Vermont reintroduced her to academia. Most of the writers there also worked as professors.

“I was kind of encouraged to pursue the academic thing,” she called it. “I had been doing self-curricular self-teaching that whole time, and then I’d gotten to a point where I didn’t really have any mentorship at all and I didn’t know how to ask for that,” she said. “I’ll just go back to school and that’ll be interesting,” she recalled thinking.

Gellatly first started college at Northern Vermont University. She also began working at the college’s literary journal, the Green Mountains Review. But she was still looking for a community of students closer to her age. Research led her to the Frances Perkins program at Mount Holyoke. “It just called to me,” she said. Now, at Mount Holyoke, Gellatly is an English major and a poetry editor at the Mount Holyoke Review.

It was the months before coming to Mount Holyoke –– the summer of COVID-19, the Black Lives Matter protests and a head injury –– that gave Gellatly the space to write “The Fever Poems.”

“Last January, I was prescribed a month of rest after a head injury and I completely cut out screens and, like, all communication with people because it was, like, a very rigid kind of prescribed rest,” she recalled.

Instead of communicating with friends over Instagram as she usually did, Gellatly turned toward disposable cameras and letter-writing. “That’s how I started doing collages,” she said.

Gellatly’s month of rest also changed how she edited her poetry. Instead of being able to edit a document on her computer, she began cutting out the words she was writing and moving them around physically on her desk. “The whole thing happened quickly and without any intention,” she explained. This technique rapidly transformed into her creative process and gave way to “The Fever Poems.” The first “Fever Poem” was created in April 2020.

“The Arctic Diary of Russell Williams Porter” was a book given to Gellatly that she originally kept for sentimental reasons. When preparing to move last spring, Gellatly found the book among her shelves. “I didn’t want to carry it around anymore, so I decided I would cut it up and make something else out of it. And then it just became another book,” she said.

Though her head injury healed and she was able to go online again, Gellatly maintained her poetry-making work ethic. The summer continued to be a transitional time, both for her as she moved, but also for the U.S. as the nation was engulfed in Black Lives Matter protests after the murder of George Floyd. Watching this transpire, “I was just sitting at my desk every day cutting up and writing poems,” she said.

The bulk of the poems took Gellatly just a day to write. “They were easy; they were, like, automatic. You know, I didn’t feel like I was really in control of that whole process. That was just happening, really quickly,” she said.

Toward the end, the pieces started taking longer to come together. One poem, “the arc light,” caused Gellatly particular difficulty. “I had it off to the side, and when I say that, you have to imagine … the scraps of these tiny little pieces over on the side of my desk,” she said.

Behind her, across the room, tiny scraps were still visible on the side of her desk.

But “the arc light” was eventually finished. The poem came out more narrative than any other in “The Fever Poems.” “I was trying not to write a myth, I guess, but on day three or something, I was like, ‘Okay fine, be what you want to be. I don’t care.’”

The time spent grappling with this piece, however, has paid off. “the arc light” shines in Gellatly’s collection for its storytelling, including the exploration of the history of a place and female connections within that location. The poem, found in part one of her book, discusses a vague but absorbing narrative of women emerging from shadows in the middle of the night with the narrator, finding the difference between “death and dawn.”

The poem “Miranda was to die,” which closes the second portion of the book, also took on a more narrative format. Gellatly mentioned that this poem feels as though it is part of the same story as “the arc light.”

“Miranda was to die” is the companion poem to the opening piece of section two, “Miranda.” Each poem centers around a character she created based on Porter’s first boat, Miranda. “She wasn’t actually the ship that, like, got them to the Arctic,” Gellatly explained. “I don’t remember the name of that one.”

In the poems, “Miranda” is often in italics, which makes the name stand out, almost as if it was designed to be a main character. Gellatly explained that this typography was a result of the name’s frequent appearance in the captions of drawings in Porter’s diary.

Porter’s book provided “The Fever Poems” with its focus on sea images, such as fog and water. It also introduced the word “fever” into the vocabulary of Gellatly’s writing.

“Fever” here, in its main usage, comes from Porter’s frequent discussions of Arctic fever, which is the obsession with the Arctic that often drove explorers to the extreme north. It’s a feeling Gellatly shares with Porter. “I’ve had [it] for a long time, [it’s] the reason that I was given this book in the first place. I had this fixation on the Arctic,” she said. “‘The Fever Poems’ is kind of my swan song to that because I’m done with those narratives.”

Gellatly continues to repurpose the word “fever” throughout her collection. She touches on actual Arctic fever, but then strays into the other literal interpretations of the word. She thought back to her two months of hives during the COVID-19 pandemic. This amounted to what she called “physical paranoia.”

“Fever” dipped into metaphor as well. Gellatly said it was “more coming from depression and trauma.” Adding, “The last 10 years, I’ve been obsessed with reading books. The Arctic was definitely kind of an escape for me. … I came to understand, too, that there’s a relationship between the impulse to go to the Arctic and this survivor kind of mentality.”

Gellatly was not alone in connecting her mental health and the Arctic. Throughout the past few years, she has come across multiple books by other women, who are survivors of various traumas, who are also drawn to the Arctic. “It’s like, if you can be there, you can be anywhere. There’s a resilience to it,” she said.

Gellatly then became engulfed in the idea of the Arctic. “I had been kind of living with a fixed narrative for a while. And I just wanted to repurpose it and see it be something else and sort of take control of that and change it and move on. It was really healing in a way,” she said.

Repurposed words are a common element in Gellatly’s poetry. In particular moments of strength throughout her book, she transforms nouns into verbs, creating familiar but jarring imagery. Gellatly said she found power in this manipulation. “It’s so surprising and when it’s happening on my table, it’s really exciting,” she said. It’s “working the limitations [of language] and trying to communicate through them,” she added.

The format of her poems is also unique, as many sprawl, wave and form shapes across the page. “[Format] is the one thing that doesn’t feel like an option when I’m writing,” she said. “So in a way, I don’t have to worry about line breaks.” She held up a piece of cut-out paper to demonstrate this: a snippet cut out with an X-Acto knife from a page of Porter’s book. There are a handful of words remaining on each line. Above her desk, these cutouts can be seen glued to their respective art pieces. They hang on the wall as if in a small gallery, giving platform to collages of paper, black charcoal and brown paint.

The knife was another key creator of “The Fever Poems.” She related how she used Porter’s book to how she, in her previous employment as a butcher, used animals.

She employed the idea of “the book as a body and butchering parts to make ingredients to make something new,” she said. Gellatly works with the idea of whole animal butchery, saying, “You have to use as much of it as possible.” She held up her first copy of Porter’s book. Across the fading brown cover were faint white streaks. “The cover of the book is my glue pad,” she said.

The visuals accompanying some of the pieces are a part of this concept as well. All drawings are clips from Porter’s observational sketches, and the windows cut into the paper to look at those drawings are made from the pages Gellatly cut words from.

This semester, Gellatly is continuing the same creative process as she works on her next book. At Mount Holyoke, she is working on an advanced project with Assistant Professor of English Andrea Lawlor and an independent study with Associate Professor of English Nigel Alderman. “They’re both about this new project I’m working on, which is the same process, butchering the book, but a deep dive into the concept,” she explained. “I was a butcher and I’m really embracing the metaphors of that, so I’m cutting up cookbooks.”

“It’s just really interesting to be staring at a metaphor,” she said. “The whole metaphor of book as body that I used to do ‘The Fever Poems’ and how different it is in this experience because in [‘The Fever Poems’], the words came first and the images were incidental. I’m trying [now] to be deliberate with both.”

“The Fever Poems” will be published on July 16. Copies can be pre-ordered on the Finishing Line Press website at https://www.finishinglinepress.com/product/the-fever-poems-by-kylie-gellatly/.

Editor’s note. Flannery Langton ’22 is also a member of the Mount Holyoke Review.