Graphic by Audrey Hanan ’28

By Betty Smart ‘26

Graphics Editor

Over a month ago, Mount Holyoke College’s workers went on strike, and I came to the realization that I had next to no idea how the College’s budget worked, both under normal and abnormal situations. While the College’s annual financial statements are available for public viewing on the MHC website, most students’ only real exposure to the budget comes from experiencing increases in tuition. I sat down with the College’s Vice President for Finance and Administration and Treasurer, Carl Ries, to break down the budget. This is part two of what I learned about the bigger picture of the College’s budget. The first part of this article can be found in Mount Holyoke News’ 9/29 publication and on our website.

How does Mount Holyoke pay for bigger projects?

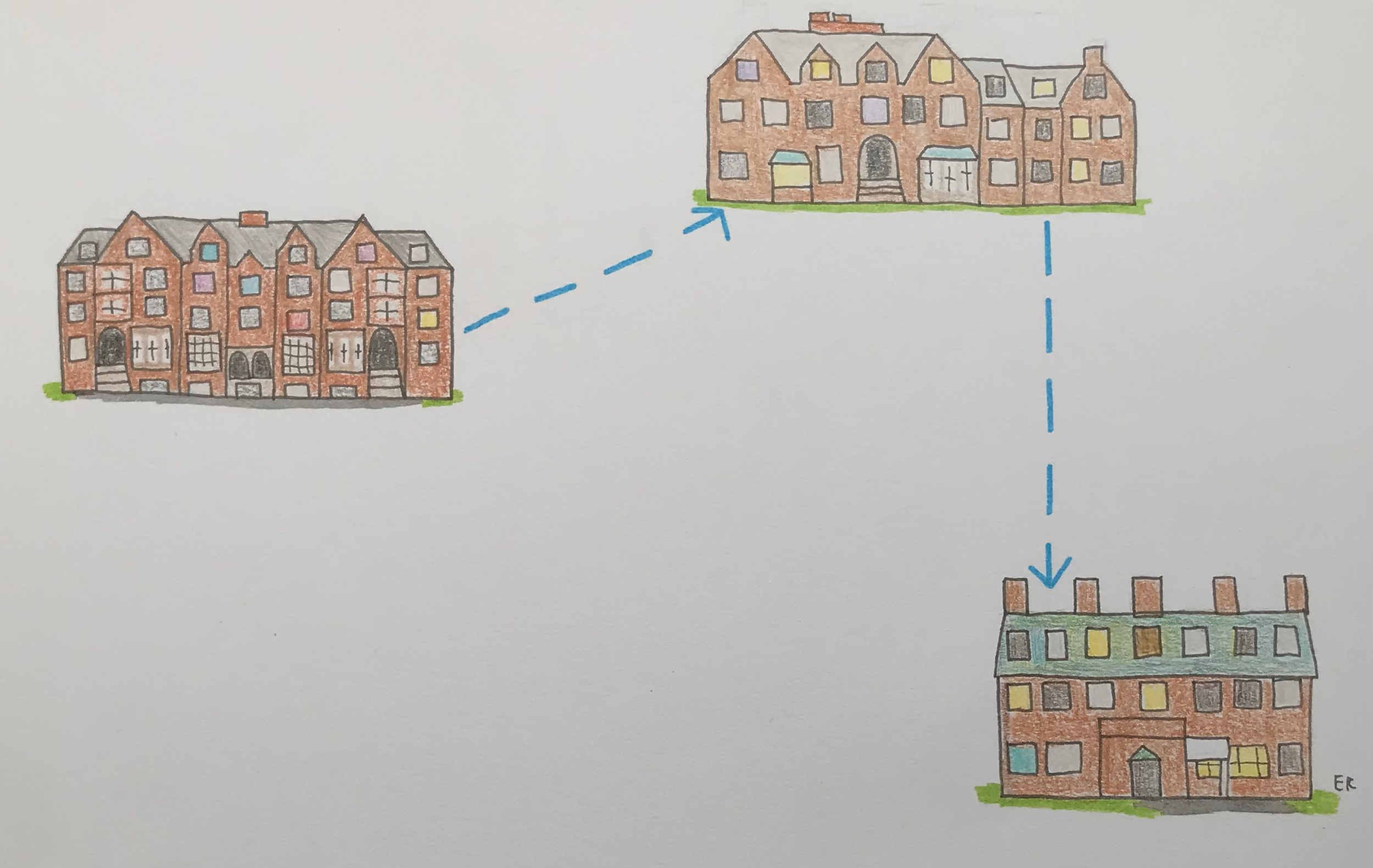

One big mystery for me surrounding the budget centered on the College’s big building and renovation projects and how they fit into the College’s financing. I learned from Ries that Mount Holyoke actually has two budgets. The first is the operating budget, which was discussed in more detail in the first part of this article, and concerns the everyday costs of the College. The second is the capital budget, which is primarily concerned with the College’s larger projects.

The capital budget is paid for with debt, the occasional grant, and, this year, $5 million out of the entire operating budget. Doing some quick math on this, out of a total budget of around $165.5 million, 5 million would be 3%. Even if this amount were entirely composed of tuition revenue, each student — 2,209 total in 2024 — would have paid approximately $2,263.47.

Putting this number with an average 2024 tuition of $44,448.16 — $98,186,000 from 2,209 undergraduates’ total tuition, housing, and food revenue — each student would have paid at most approximately 5% of their total tuition towards the capital budget.

Ries went into this in more detail, saying the College “[doesn’t] use regular revenue to support [bigger projects.]” Because the funds in the College’s endowment are protected and hence cannot be used, the College can either fundraise, or take out a loan. Previous projects like renovations to the Community Center and construction of “SuperBlanch” were a mixture of both; “a little bit of borrowing, but mostly fundraising,” according to Ries.

Depreciation of buildings in general is another big expense for the operating budget. A hypothetical building that is initially worth $50 million, according to Ries, would go on the College’s balance sheet as an asset. As time goes on, however, its value would fall; going off an estimated useful life of 50 years, that would be an annual loss of $1 million from its original value. This loss is what “hits [the] operating budget as depreciation,” according to Ries; while depreciation isn’t directly spent, like other expenses, the reduced monetary value it represents counts as a loss. Last year, depreciation cost the college $12,280,000, about 7% of its total expenses. Ries went on to say, “This last fiscal year … is probably the first year in which we will have had a deficit from operations. And a large portion of that is because of increased depreciation.”

What happens in the case of budget deficits or surpluses?

According to the College’s annual financial summary, Mount Holyoke ended the 2024 fiscal year with a deficit of $452,000, which was a noticeable change from the previous year’s surpluses. Ries said this was something that hadn’t happened in “several years.”

The College’s 2024 financial summary partly attributes this drop to “reduced vacancies,” particularly following COVID-19. “For years after COVID, when people weren't coming back to work as quickly, or it was harder to find employees to fill those positions, we saved a little bit of money because we weren't spending as much money on personnel,” Ries stated.

Despite the “very small” surpluses, the College had no intention to continue with a smaller staff, as Ries told me, “Being fully staffed is important because if the Dining Commons isn't fully staffed or if Student Life isn't fully staffed, that means that the students are not getting the experience that we want them to have.”

According to the 2024-2025 financial summary, the deficit is the result of increasing wages and benefits, and more work being done on buildings and their subsequent depreciation. In situations like this, deficits are covered with reserves. These reserves are not from the endowment, instead they are made up of surpluses from previous years that earn interest in the operating account funds. “We can cover a few years of operating deficits through the use of reserves, but they’re there [for]support when times get tough,” Ries said.

In what other ways does the College respond to inflation?

Inflation is all around us, and not going away anytime soon. Ries told me that while Mount Holyoke is unfortunately “not large enough” to stock up on heavy equipment like that for the building projects, the rising cost of food is another story. The College does not want to have to stop doing business with local suppliers because of rising prices. “We do a ton of local purchasing, so we try to avoid [choosing different products] as much as possible.”

“One thing that they were talking about doing this year,” he went on, “was ordering a larger quantity of a particular ingredient, prepping it … ahead of time, [and then] freezing or refrigerating it to then be used at specific times in the year.” Ries said the biggest questions the College tries to answer when doing this are, “How much does it cost to buy a certain ingredient? Should we be buying it prepared, or do we do it from scratch the way we do it now?” Ries gave me an example, saying that for the College, “buying pre-chopped onions is very expensive, [but] buying a box of onions and paying somebody to do it has been cheaper for us.”

All in all, Ries said, the College’s efforts around inflation boil down to “choosing products, thinking about preparation … and avoiding all the sort of ancillary costs of buying stuff that comes shipped in from California or from Florida because there’s an environmental impact, there’s a cost to that. So we try to do as much local [purchasing] as we can.”

What would happen with a loss of federal funding?

Although a loss of federal funding is a real possibility, the College is not in over its head yet. Overall, it truly depends on the extent and nature of the losses. Regarding something like a hypothetical ban on international students, Ries said the College would immediately “have to stop everything and figure out how to deal with that … there's no contingency that can really prepare you … you'd have to restructure a lot of the budget.” However, for certain smaller things, the College is more confident. Ries said certain losses could be made up for by fundraising, or outside grants or philanthropy. “It may mean that we'd have to cut expenses in a certain area, but we haven't had to do that yet … Some of it is really thinking about, ‘Do we have to make changes to the operating budget or can we replace that revenue?’”

An example Ries gave was Pell Grants, a federal program that pays financial aid for those it describes as “undergraduate students who display exceptional financial need,” and usually does not need to be paid off. If the College were to lose access to them, it would likely turn to privatized student loans, something that it is already doing for international students.

Right now, 70% of all undergraduate students at Mount Holyoke apply for financial aid, and 82% of those applicants receive some aid from grants they don’t have to repay. Ries said that no matter what, the College would always prioritize its students. “We have a commitment that we've made to them, and it would depend on the long-term impact, but the College would find a way to make sure that we didn't lose students because of a loss of federal funding. That's something that we've been saying since the beginning of all of these threats, that we'll find a way to make it work.”

Madeleine Diesl ’28 contributed fact-checking.