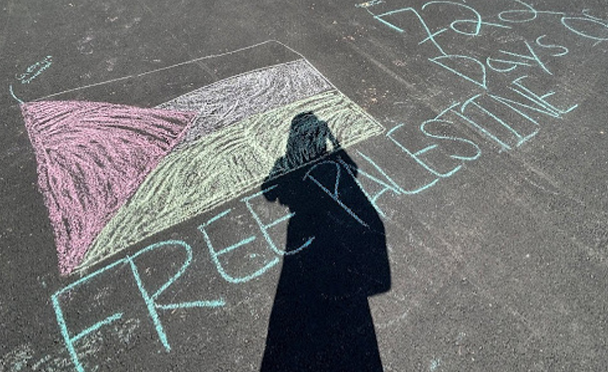

Photo by Anna Goodman ’28

Some Mount Holyoke College students have been chalking on the roads and pathways around MHC’s campus with messages in support of Palestine.

By Anna Goodman ’28

Staff Writer

Content Warning: this article discusses genocide at length, as well as famine, antisemitism, mass murder, Islamophobia, and the Holocaust.

I’m eight years old, swinging my legs because they can’t touch the floor yet, the first time I consider myself Jewish. It’s April 2015 and hours past my bedtime when a friend of my father begins the fifth of — what seems to me as — endless Passover readings, and I don’t understand why any of them matter.

I don’t go to Synagogue. I don’t speak Hebrew. I eat Challah bread on Friday evenings and pretend to like grape juice, and that’s about it. But that has never mattered to my family, because to us, being Jewish is not just a religion, but also about the preservation of our culture. In truth, an act of defiance.

Yet, despite my boredom, it’s at this table, at eight years old, that I start to understand that defiance. To grasp what the Holocaust was. And I don’t understand. How could anyone let this happen?

Later, it’s December 2023 and I’m sitting at my desk as my teacher recounts the week’s news. I sit there as my classmates debate terrorism and occupation and retaliation and who deserves to die screaming and who’s innocent. For perhaps the first time in my life, I bite my tongue.

Because I am not thinking of the people in my class. I’m thinking of family. Of a man — a boy — I consider like a brother, who was drafted into the Israeli Army just after he turned eighteen. Who, for safety reasons, I will refer to by the Hebrew word אחי: “ach-khee,” literally “brother,” but in colloquial use, close male friend.

אחי is only six months older than me. He messaged me the other day and asked if I was also getting gray hairs.

And a part of me feels for him. Another part doesn’t know if I should.

Just this year, several experts at the United Nations declared, “While States debate terminology — is it or is it not genocide? — Israel continues its relentless destruction of life in Gaza … massacring the surviving population with impunity. … No one is spared — not the children, persons with disabilities, nursing mothers, journalists, health professionals, aid workers, or hostages.”

In the six months since, the scale of destruction has only gotten more horrifying.

As of Nov. 29, 2025, “Palestine’s official health ministry has tallied the dead at over 70,000”: An already horrific number that many experts have stated is likely a severe undercount.

By the Israeli military’s own numbers, every five out of six of those people were civilians.

“Every genocide depends on the dehumanisation of its victims,” Guardian reporter Owen Jones wrote, “Mainstream media outlets have airbrushed the truth about Israel’s genocide — whether that be broadcasters or newspapers. They’ve failed to report multiple atrocities, failed to show the horrific consequences, repeatedly regurgitated Israeli lies about their war crimes. ”

Entire textbooks could be written about the horrifying dehumanization of Palestinian people, Palestinian children in particular. But I’ve seen much less said about the opposite: The almost gentle language and strangely subdued anger surrounding the people committing these atrocities.

Every Nazi — from the guards at the camps who pulled the levers on the gas chambers to the everyday enablers who registered party membership just to keep their heads down and live, to those who shut their windows and turned away from the people with pinned yellow stars being dragged down the street — was a person who made a decision, just like אחי.

And when we wave our hands and say things like, “well, they had no choice”, or “well, that’s not the same,” we clear the path for ourselves to expunge our own guilt.

“I didn’t do anything!” But, see, that’s the problem, isn’t it? You didn’t do anything.

There’s a very famous poem called “First They Came” by German Pastor Martin Niemöller, that I’m sure many of you have heard before. “When they came for the Jews,” it says, “I did not speak out because I was not a Jew. Then they came for me and there was no one left to speak out for me.”

We read it every year at Passover. We recount the story of the Holocaust, raise our glasses to those it stole from us, dip our bitter herbs in saltwater. We promise them, promise ourselves, that we will never forget.

Perhaps, the darkest truth is that we haven’t forgotten. And what does that tell someone? What does that tell not only the Palestinian students on our campus and across the country, but every Muslim person with the right to exist in a world that hates them for no reason? That they’re lesser? Unworthy of basic human decency?

“The fact that you’re Palestinian, you have to prove that you’re not a threat, you have to prove that you’re not an extremist, you have to prove that you’re just a human,” Mahmoud Khalil, a Columbia student whose arrest earlier this year sparked a whole spate of protests, tells Zeteo.

Did you know that the word אחי, brother, in Hebrew, is the same as أخي , brother, in Arabic? Why is my “אחי” worth any more than theirs?

I am ashamed to say, in the last two years, most days I tried not to think about Gaza. I donated, I protested, I cried, I declared that I would do something. I decided my empathy made me morally superior. And most of the time I couldn’t bear to even read an article, much less write one.

The truth is, I could have written this any time in the last two years and I did not, because I was just too scared. And in a decade, in two, in three, how am I going to answer when one of my students raises her hand and asks me what I did when I watched a genocide happen in real time?

“I felt bad,” I’ll say. “I pretended that that meant something.”

Now, it’s October 2025, and I’m eighteen years old. I sit down at my desk to write this article. My feet touch the floor now. It’s been 10 years since that first Passover, two years since this genocide began, and I understand now.

It’s so painful to realize that you are now one of the people whose inaction you condemned, back when you didn’t have any reason to be scared.

Through it all, I come back to אחי. Who got his friends to help him fake a scar so he could get a permit to grow out his hair. Who admitted to me once that his knowledge of Christmas is based on movies, and then asked for recommendations on the worst ones I could think of.

Who I couldn’t tell I was writing this article, because it would get him thrown in jail. I see his shadow in every headline. I feel my stomach twist when I remember, every time we complain about our coworkers or share anecdotes about our moms, that his hands are bloody.

And still I fear that someday I’ll wake up to a call from his little brother telling me that he’s gone, and I won’t know what to do with myself.

Now, just imagine that same fear, that same agony, multiplied tenfold, for the people whose loved ones are, or, were, Palestinian. Who have crawled out of the rubble of the places they called home over the bodies of the people they called Mom.

“Gaza has become a place where death is so constant and survival so compromised that even silence now speaks louder than any appeal for justice,” Muhammad Shehada wrote for the joint Israeli-Palestinian newspaper +972 on the second anniversary of October 7th. “And the legacy of this genocide will be with us for generations.”

The legacy of this genocide, as much as we would like to live our lives not admitting to it, is on America’s hands too. For the last two years — and decades before then — it’s been America’s bombs, America’s missiles, America’s money enabling the Israeli army to rage a campaign of abject violence and terror on civilians. Our tax dollars are killing people, and our government has been, at best, quiet, at worst, actively promoting it.

“The decision is stark,” the UN stated in its official report on Gaza: “[we can] remain passive and witness the slaughter of innocents or take part in crafting a just resolution. The global conscience has awakened, if asserted - despite the moral abyss we are descending into - justice will ultimately prevail.”

“Right now the Israeli government is waging a genocidal war on Gaza,” the organization Jewish Voice For Peace says in their mission statement, “claiming the support of all Jews who live in the US… we say, ‘Not in our name!’”

And I may not go to Synagogue. I may not speak Hebrew. I eat challah bread on Friday evenings and pretend to like grape juice, and really, that’s about it. But when it comes to defiance, I am as Jewish as my ancestors.

In his response to Niemöller’s “First They Came” poem, written in the wake of the 2016 election, American Rabbi Michael Adam Latz said, “Then they came for the Muslims and I spoke up—Because they are my cousins and we are one human family … They keep coming. We keep rising up. Because we Jews know the cost of silence. We remember where we came from. And we will link arms, because when you come for our neighbors, you come for us—and that just won’t stand.”

It would be naive to say that writing an article that will reach a thousand people at most will cause any tangible chance or will save any lives. But it is still something.

I may be a child. But so is אחי. So were the countless people and their אחי s, their أخي s, who have died at his army’s hands.

And I am Jewish.

I remember where I came from. I remember all those Passovers spent listening to the stories of the Holocaust. I know the cost of silence. I know the power of linking arms. I stand on the shoulders of all that came before me, all those who lived and died and fought for a better world. And on their behalf, I say: not in our name.

Angelina Godinez ’28 contributed fact checking.