Graphic by Vivian McPherson ’23

BY CASEY ROEPKE ’21

In the wake of the 92nd Academy Award Ceremony, in which no women were nominated for the Best Director category, many were outraged at Hollywood constantly overlooking female direction. Actors and directors alike came out in support of movies like “Atlantics,” “Queen & Slim” and “Honey Boy,” three feature directorial debuts by women considered to be some of the best movies of 2019. Critics of this latest Oscars snub were quick to post to social media and speak to journalists, many echoing similar sentiments: that women can direct movies just like men.

“Portrait of a Lady on Fire” proves this statement wrong: women direct movies both differently and better than men.

Director Céline Sciamma intentionally cultivates a world within this film in a way that is refreshing, new and completely, utterly motivated by her identity as a lesbian woman. Sciamma de-centers men to the periphery of the film as an act of liberation, and the women that fill the space don’t waste their time complaining about their disempowerment in 18th century France; why would they complain to each other about the patriarchy when they all share daily lived experiences of misogyny? Why do period dramas centered around women spend so much time talking about their frustrations with the patriarchy and male-dominated society? The women in “Portrait of a Lady on Fire” know the world they are in. They do not seek to compare wounds, only to find solace and solidarity in each other.

The movie begins with a framing device: Marianne (Noémie Merlant), a painter, poses for a group of women who, in short bursts of interceding shots between title slides, tentatively sketch her outline. One of the students brings out the titular portrait and Sciamma brings the viewers into retrospect. This short period of time shows when Marianne is commissioned by a wealthy woman to paint a portrait of her daughter for a Milanese suitor. The primary problem: Héloïse (Adèle Haenel) refuses to sit for a painter, and so Marianne must study and paint in secret. Sciamma emphasizes long, sparingly-cut scenes in which Marianne looks at Héloïse to highlight the transition between examination for her secret employment and the later, gentler, more desperate gaze of longing and desire.

“The tension around the gaze is the plot of the film, you could even see it as a manifesto around the female gaze,” Sciamma said to the Los Angeles Times.

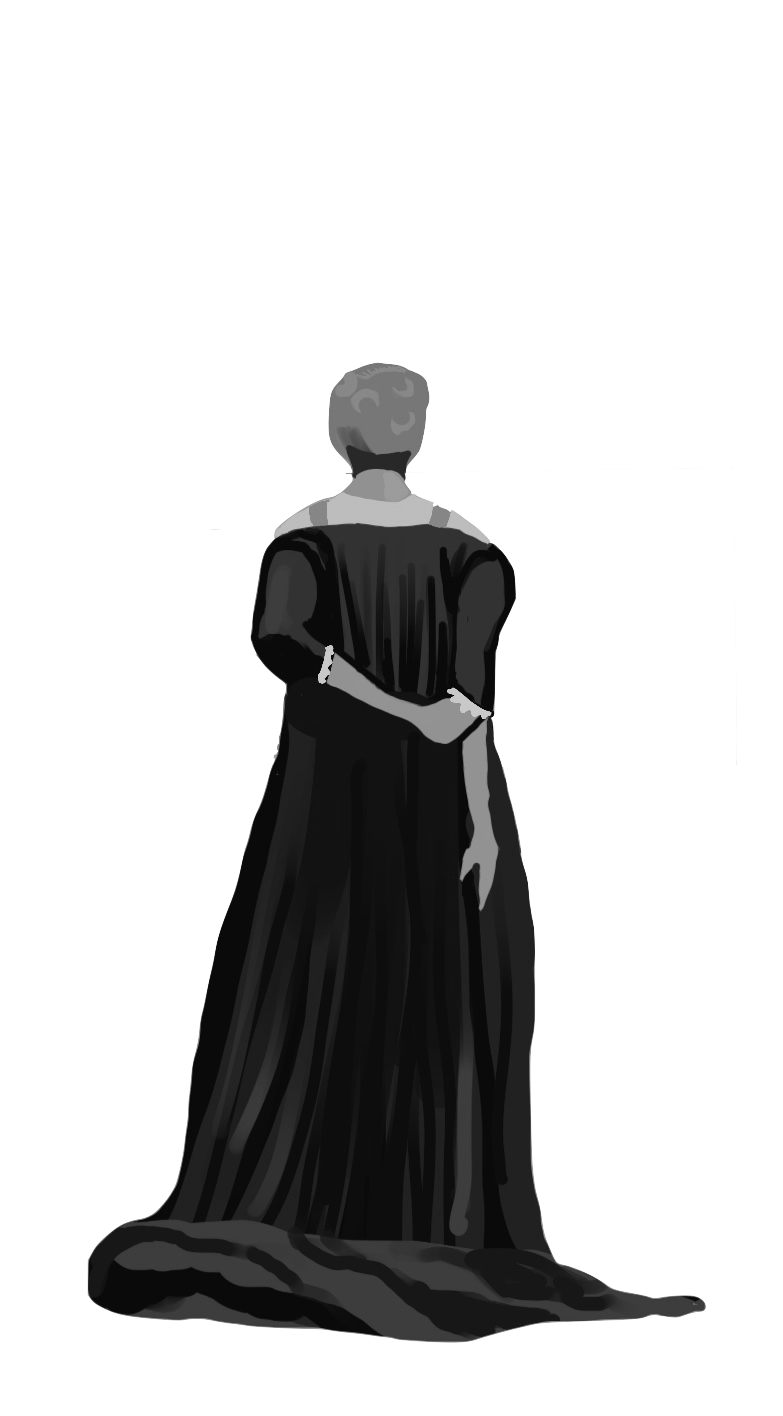

Sciamma unpacks the “male gaze” with each close, intimate shot. In their first meeting, Marianne sees Héloïse from behind. The camera follows Héloïse’s hooded figure, leaving a polite distance between her and the camera. The seconds stretch tantalizingly and suspensefully before Héloïse’s face is revealed, which mirrors the major conceit of the film: It is a commentary on looking and being looked at, about seeing and being seen. Marianne fails in her first portrait of Héloïse because she is too set in the conventional art norms of painting within the male gaze; it is only after Héloïse consents to pose for a portrait that Marianne is able to see outside the bounds of masculine art.

Sciamma further equalizes the two women in granting Héloïse the power to vocalize her observations of Marianne, even as Héloïse is supposed to be an object of observation herself. The dynamic between the two women, as they slowly enter an intense and passionate romance, never feels uneven. The two are equal in their pursuit of — and desire for — each other.

As much as this movie is about their romance, Sciamma also creates a masterful work of poioumenon — a story following the process of artistic creation. The shots of Marianne painting are close and force a perspective as if the viewers themselves are holding the paintbrush, bringing the audience intimately into the world of the film.

In “Portrait of a Lady on Fire,” Sciamma directs a period piece as beautiful and devastating as real life. Marianne is uninhibited by her dresses, moving furniture and hammering wood as though she were unwatched by an audience. In one scene, she wakes up with menstrual cramps; in another, she paints a recreation of Sophie (Héloïse’s maid) undergoing an abortion. These images, though normal and natural, are revolutionary in their portrayal on screen.

The characters share common experiences of living as women in a deeply sexist society, but are also separated by class and occupation. When Héloïse’s mother leaves the house for a few days, Marianne, Héloïse and Sophie shed their formal garb and the contrived class inequalities between them.

Like Bong Joon-ho’s “Parasite,” Sciamma unravels social classes and socioeconomic positions. Like Greta Gerwig’s “Little Women,” Sciamma’s portrayal of women is both political and apolitical. I compare “Portrait of a Lady on Fire,” to other movies not be- cause the film is derivative or trite — it is quite the opposite — but because it is hard to capture the simple fact that it is unlike any other movie. Although the cinematography is exemplary, the dialogue is award- winning (Sciamma is the 2019 recipient of the Cannes Film Festival Award for Best Screenplay) and the music haunting. Perhaps the most incredible aspect of the film is its ending.

“What is a happy ending in a lesbian love story?” Sciamma asked in an interview with Autostraddle. “Eternal possession? We want a frozen image of two people getting married? We have to tell our own narratives regarding how we lead our lives and how we love.”

Sciamma continued, “talking about the different power dynamics in a lesbian relationship is the first thing. Then building a love dialogue without expected conflict, departing from love as conflict, love as a bargain. Saying that love is fulfilling! Love can be emancipating!”