BY SARAH CAVAR '20

Since 1982, the American Library Association (ALA) has celebrated Banned Books Week, which both acknowledges the censorship that affects hundreds of books every year and celebrates the right to read these works.

The ALA has collected reports documenting bans and challenges on books in libraries and schools across America, compiling them on their website in order to share trends and statistics in the banning and challenging of books. Banned Books Week 2017 (which was between Sept. 14 and Sept. 30) concurred with a growing trend in censorship, as shown by the ALA: the increased targeting of books based on “sexual” — and especially LGBT — content.

For a book to be considered banned or challenged by the ALA, it must have been challenged in at least one school or library. The ALA’s list is derived both from media coverage of censorship and from challenge reports submitted directly to them. These challenges reflect “an attempt to remove or restrict [reading] materials, based on the objections of a person or group.” Most often, these challengers are parents. Of the 5,099 book-challenge reports sent to the ALA, 2,535 were made by parents. Reports indicate that clergy members, contributing only 24 of the 5,099 book challenges made, were the least frequent challengers.

“Sexually explicit content” has been a reason behind 1,577 of the 5,099 total books challenged between 2000 and 2009. Although this data is eight years old, the disproportionate focus on sexual explicitness as reason enough to ban a book is also reflected in the list of 2016. Of the top 10 most banned or challenged books of 2016, seven of them can attribute their challenging to so-called sexual themes. Comparatively, none of the top 10 most banned or challenged books can attribute their status to war or violent content.

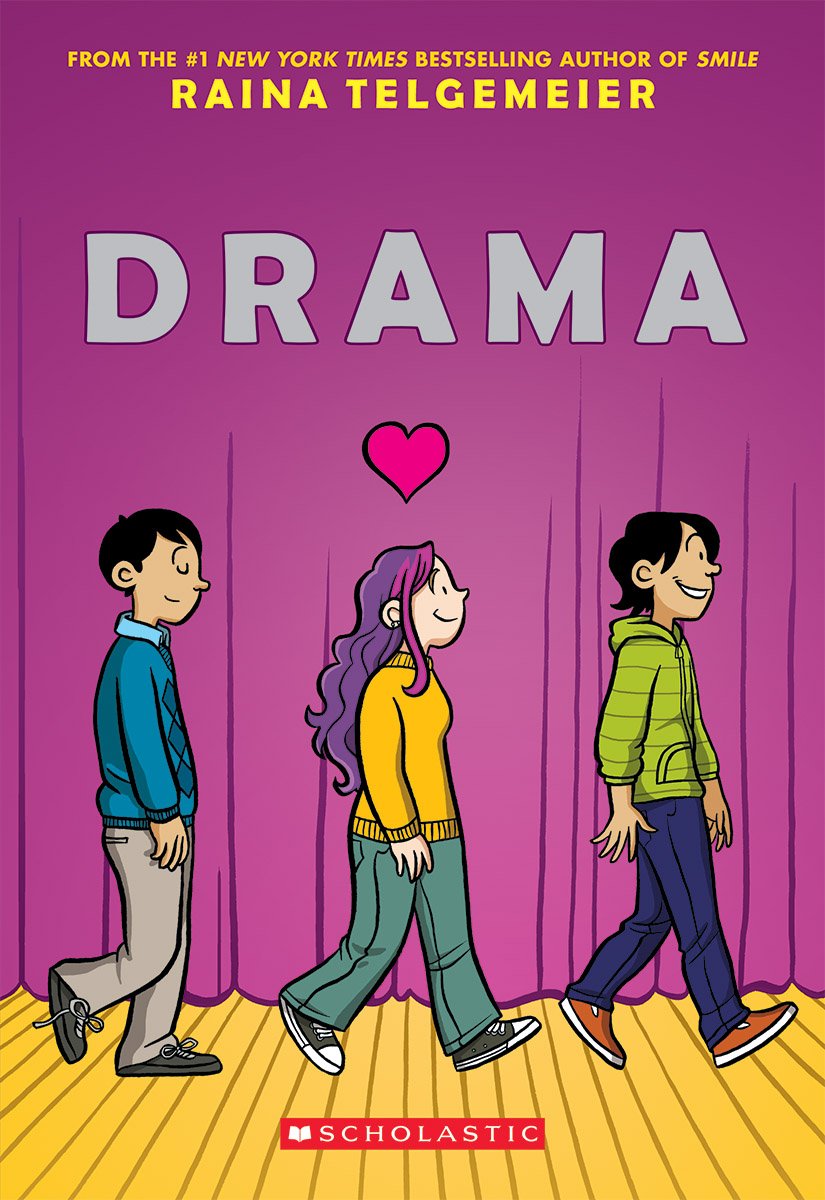

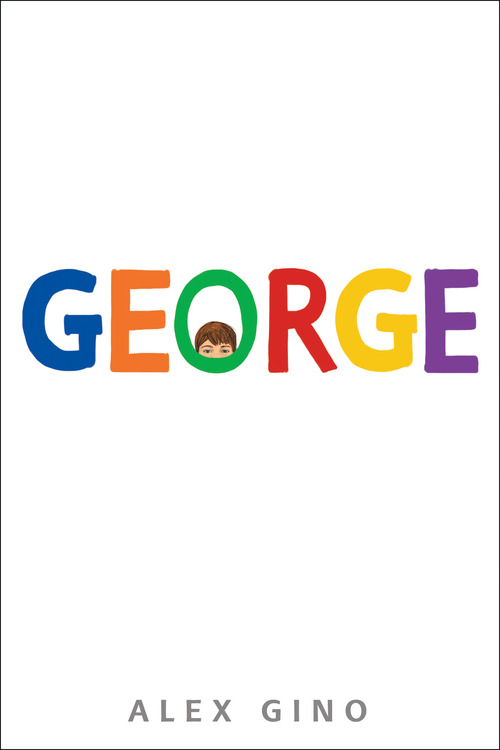

Five of the top 10 most banned and challenged books in 2016 contained “LGBT content,” and two of them contained transgender content, specifically.

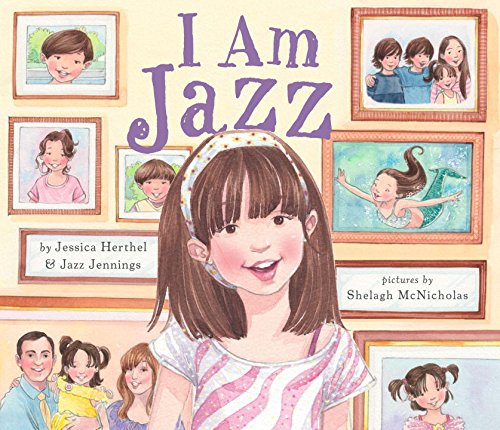

The fourth most banned book of 2016, “I Am Jazz,” covers the life experiences of transgender teenager Jazz Jennings, written by Jennings herself with the help of Jessica Herthel. Jenings’s vocal advocacy for transgender youth has since launched her into fame. The book was said to contain, among other things, “[offensive] language, sex education, and offensive viewpoints” that resulted in its banning. The most popular reason for its challenging, however, was “because it portrays a transgender child.” This reflects an upward trend in the banning of books due to alleged sexual explicitness and “sex education,” up to eight in 2016 from three in 2002, as well as authorship by transgender people.

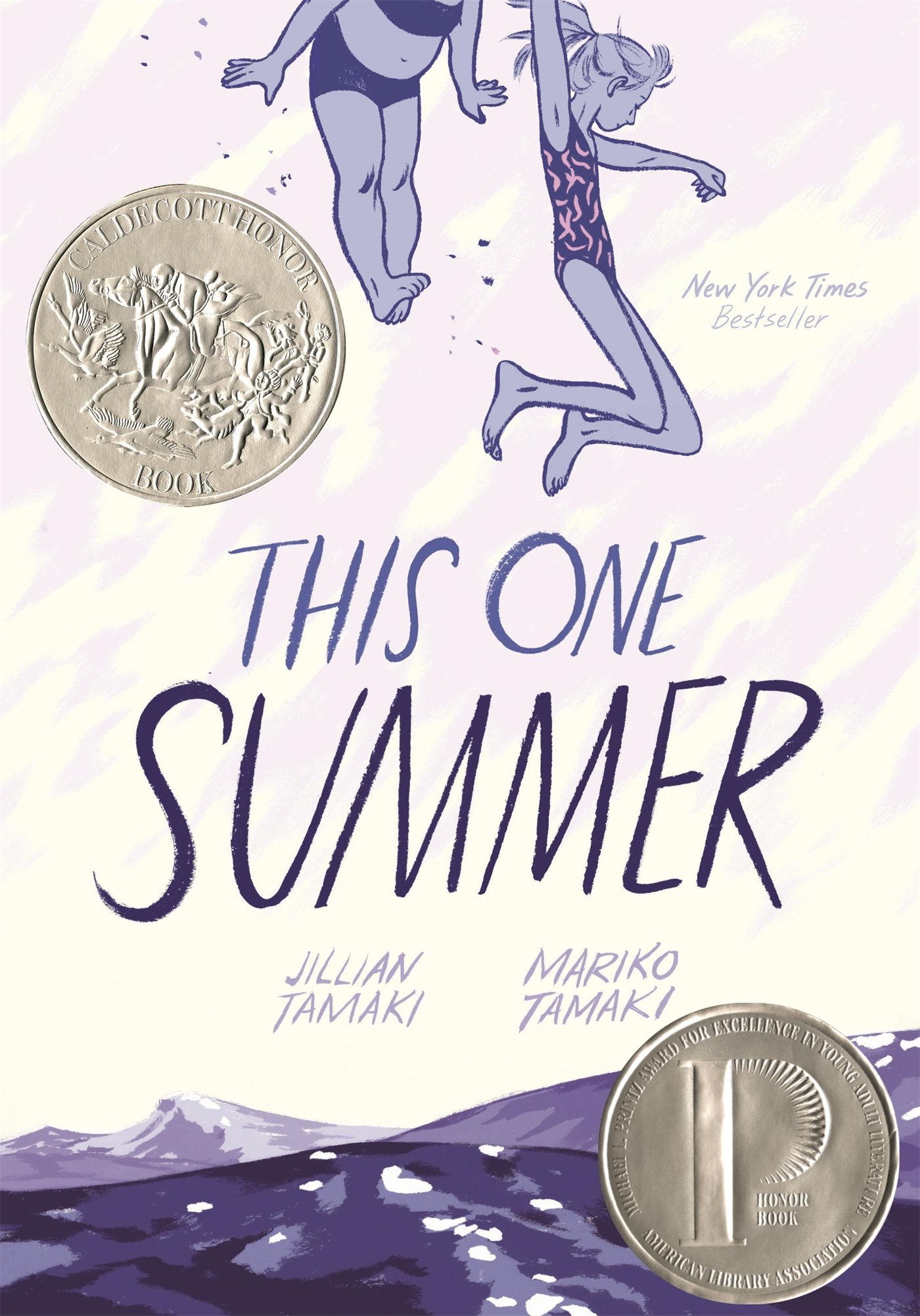

In 2016, the number one most banned or challenged book was “This One Summer” by Jillian and Mariko Tamaki. The young-adult slice-of-life graphic novel published in 2014 explores adolescent womanhood in the tradition of both Judy Blume and Lauren Myracle. As the reception and banning of Blume’s and Myracle’s respective works suggests, the release of Tamaki’s graphic novel has been met with controversy. “This One Summer” centers the complex interior lives of teenagers as they explore identity, family and sex. These themes inform the reasons for its banning as listed by the ALA: “includ[ing] LGBT characters, drug use and profanity, and [being] sexually explicit with mature themes.”

The overwhelming majority of these books are banned or challenged by parents, not libraries or schools. Miranda Wheeler ’19, whose parents are members of the Church of Christ, knows firsthand what it means when parents ban books from their children. Although her childhood school banned books, such as “Captain Underpants,” Wheeler sees a notable difference between school censorship and that done by parents. “’When my high school teachers said ‘absolutely do not read ‘The Communist Manifesto’ or ‘Go Ask Alice,”’ that’s exactly what I did.”

The difference between school book banning and parental book banning, for Wheeler, was that parental banning was intimate and guilt-inducing. Unlike the banning of books in school (against which she easily rebelled) her parents’ book banning made her “afraid to question religion” and to “explore sexuality or identity or privilege or scientific validity” and more.

PEN America, which has been working to defend free literary expression since 1922, agrees: “Teachers, principals, administrators, librarians and others must take a firm, united stand against depriving entire populations and communities of books that may be uncomfortable for some [parents].” When young people are denied books representative of their own experiences, advocates argue they are denied essential pieces of themselves.

Banned Books Week won’t officially return until 2018, but until then, there are numerous resources available on celebrating the right to read. LITS librarians have arranged a table of banned books to look through during the week, and are always available to recommend banned books to you.

All of the top ten most banned and challenged books of 2016, as listed on the right, are available at Mount Holyoke through LITS and the Five College Library Catalog — free for all to enjoy.