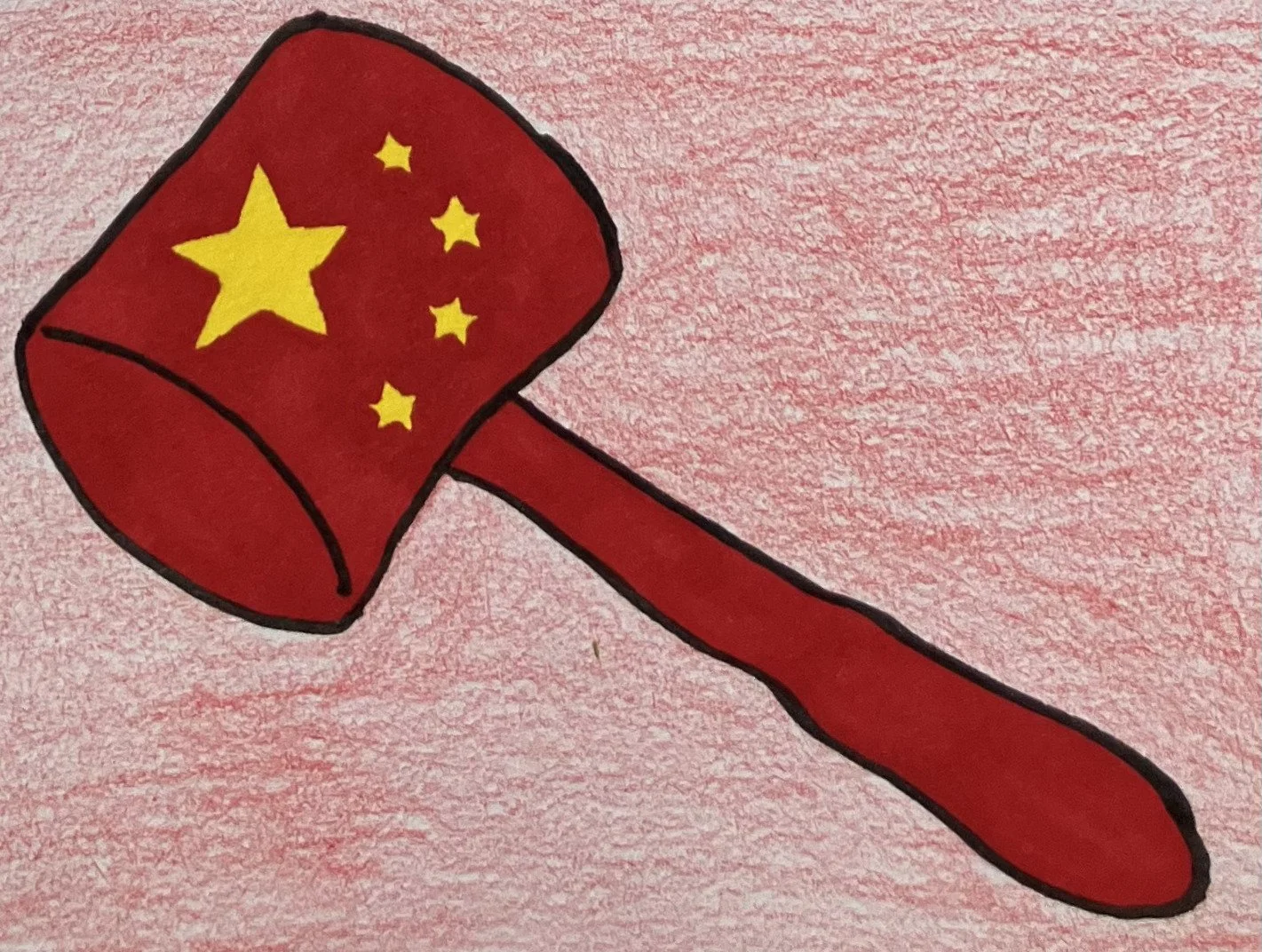

Graphic by Betty Smart ’26

By Kennedy Olivia Bagley-Fortner ’26

Staff Writer

On Nov. 21, Yutian An ’13 returned to Mount Holyoke College to present her collaborative research on how juries extend judicial power in China. During her time at Mount Holyoke College, An majored in political science and economics. Currently, she is a Ph.D. candidate in politics at Princeton University, and in January 2026 she will join the UCLA School of Law faculty as an assistant professor.

An “examines how legal systems structure state-building activities, sociopolitical legitimization and administrative entrenchment in both authoritarian and democratic regimes, with a focus on criminal law institutions.”

An began her lecture by sharing the framework and hypothesis of her research, which surround the judicial system in China. While China is led by an authoritarian government, “we should not assume that judicial institutions are irrelevant to political life in authoritarian politics.”

Through her research, An wants to ask and answer these questions: Why are autocrats turning towards law? How can a legal institution create support for the regime? Similarly, she wants to show how authoritarian leaders solve the participation dilemma without creating backlash against the regime. Finally, she wants to reflect on the importance of the lay assessor system. While the lay assessors might not understand everything about a given case, she highlights that they are an important part of Chinese politics.

In 2018, the People’s Assessors Law was enacted which made “improvements for lay participation.” According an article by Zhiyan Guo’s in the Chicago-Kent Law Review, the People’s Assessor System can be divided into three phases starting from the late 1970s to 2018: The Restoring Phase, Fast Development Phases, and the New Era, which is what An focuses on.

While China doesn’t have an explicit “jury system” like other countries, they utilize people’s assessors, who, with the judges, form a panel to hear cases. Most ordinary cases consist of a three member panel which has one judge and two jurors. A high profile case would consist of a seven member panel: Three judges and four jurors.

The People’s Assessor System allows assessors to “attend hearings in civil, criminal and administrative cases involving public interests, [which] attract widespread public attention or have crucial social impact,” stated Li Chenglin, an official from the Supreme People’s Court in an interview with Dawn News.

In her lecture, An discussed her research which examines why autocrats are turning towards the law and how a legal institution can create support for the regime. According to An, the institutionalization of the lay assessor system in China serves to “promote democratic participation in judicial decision-making, enhance justice and improve judicial legitimacy.”

As China Justice Observer reported, “the people’s assessors have equal rights and obligations as judges. Therefore, in court, they sit at the bench,” and the assessors have the same ‘one person, one vote’ right. In these ways, the Chinese lay assessor system is significantly different from the American jury system. In America, anyone can be summoned to participate in a jury case, but in China not everyone is allowed to participate. In China, there is a designated pool of assessors and they are selected every 5 years. There are about 300,000 assessors, which is only 1 out of 4,000 people.

With this in mind, An transitioned to her last segment of her lecture: The “why” behind the lay assessors. Since China is a single-party authoritarian state, how and why could there be “democratic participation" in their judicial system? Through her research, An comes to various conclusions.

Her general theory is that autocrats establish participatory institutions for various benefits. In the case of China, she argues these institutions neutralize political opponents, reduce information asymmetry and increase governance quality, and can generate legitimacy effects through participation which in turn creates a sense of voice.

However, these institutions also show the dilemma of authoritarian participation. To the general public, lay assessors and similar institutions can be seen as performative and a political show, which could negatively impact the authoritarian regime. According to An, once people begin to enter the sphere of political participation, they might want more participation. This then leads into An’s point about the way in which the government’s legitimacy might decrease because of this greater political participation.

To conclude her lecture, An showed her empirical data about how effective the lay assessor system is. She found that, based on interviews, most assessors don’t actively engage or participate during the trial. Additionally, she found that people had little knowledge about the lay assessor system as a whole.

She did find that there was a high supply and demand for lay assessors. According to her research, 83.5% of Chinese citizens were willing to serve as a lay assessor; however, she also found that many Chinese citizens don’t understand the job of a lay assessor is. Almost 77% think that jurors should have some form of expert knowledge, which is different from the American context, where jurors are expected to judge fairly and neutrally, without having any background knowledge.

Her findings led her to two major hypotheses: Firstly, that the existence of jurors would help create the perception of fairness; secondly, jurors with voting power would enhance the perception of government legitimacy.

Maeve McCorry ’28 contributed fact checking.