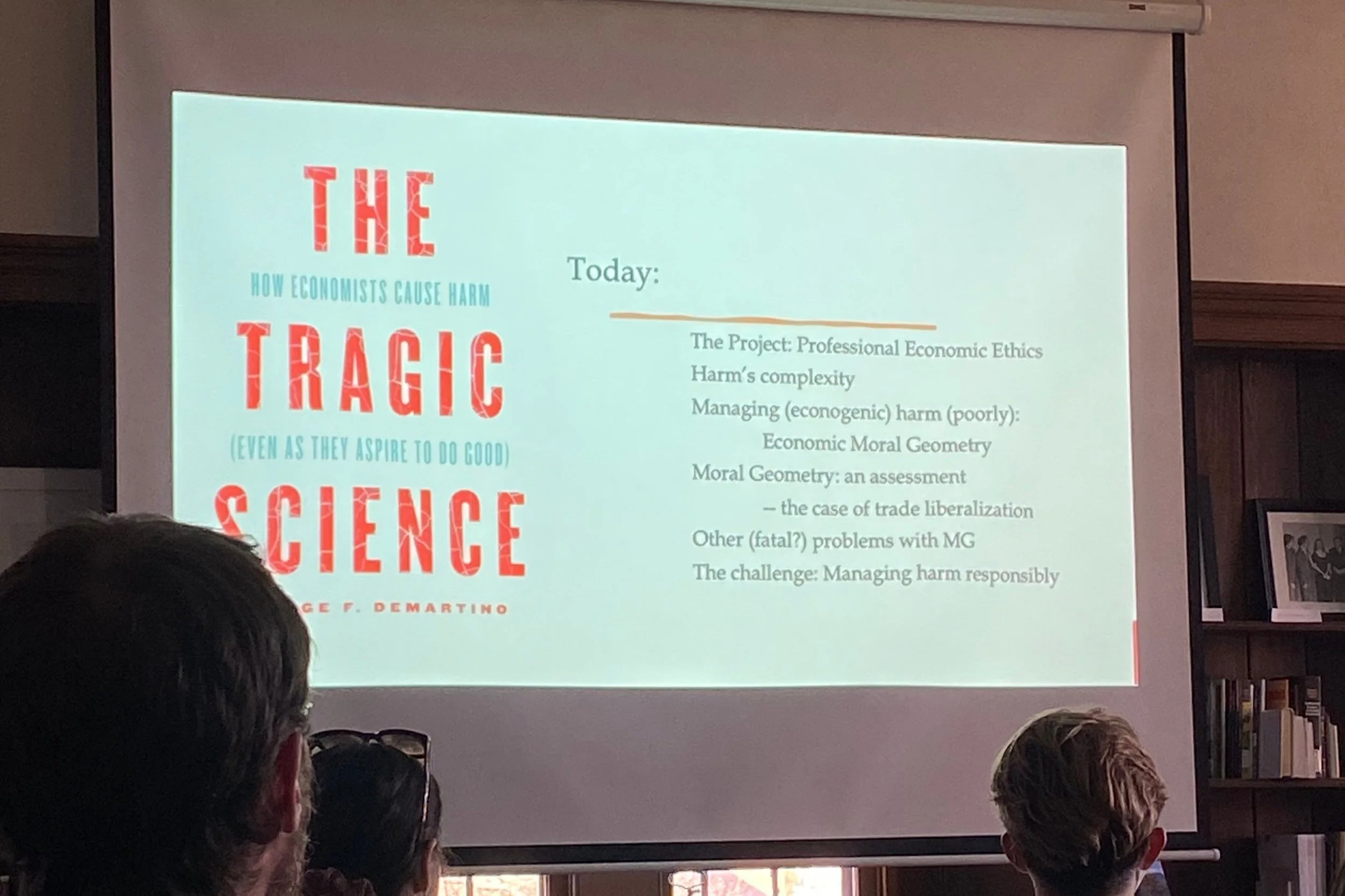

Photo by Nina Sydoryk '25. Community members gathered in the Stimson Room on April 12 to listen to Professor DeMartino.

Nina Sydoryk ’25

News Writer

Throughout the 20th century, the field of professional economics has had an increasingly influential role within the realm of policymaking. Now, professor and scholar George DeMartino says it may be time for economists to step back.

DeMartino is a professor of international economics at the Josef Korbel School of International Studies at the University of Denver. He holds a doctorate degree in economics from the University of Massachusetts and specializes in political economy, professional economic ethics, international trade and economic harm.

In his recent talk at Mount Holyoke College, which took place in Williston Memorial Library’s Stimson Room on April 12, he discussed some of the topics outlined in his most recent book “The Tragic Science: How Economists Cause Harm (Even As They Aspire To Do Good).”

DeMartino’s initial presentation centered around the theme of harm in economics, and how the grossly important question of economic ethics has gone largely unconsidered by its internal community.

“The project I’ve been involved in for the last 15 years or so is to create a new field of scholarship that doesn’t exist,” he began.

“Most professions that have influence over the lives of others have [a body of professional ethics] associated with the profession and the professional training … In some fields this is very well developed, such as in medicine, law, journalism and so forth … in economics, we’ve had none of that for … well over 100 years,” DeMartino continued.

He emphasized that while economists have written to the American Economic Association to inquire about an economic code of ethics, the answer that is given to them remains the same: It is not needed. DeMartino maintains that it is and that economists deal with issues on very large scales based on the theory of quantifiable and compensatory harm.

The professor argued, however, that there are some harms that may not be compensatory, and that economists are trained to think about harm through what he calls “moral geometry.” In essence, economists work under the assumption that there are some means of compensating an individual to bring them back to the state of happiness or utility that they possessed before.

He uses the instance of the Sioux Nation being offered money by the United States government as means of compensation for the violation of the Fort Laramie Treaty and subsequent removal of land in 1868. In the pursuit of justice, the Sioux have continuously refused this monetary compensation. The message from the United States government is clear: land being returned to the Sioux is not under consideration. Thus, by choosing to not accept the money, they enforce the notion that not all harms can be remedied with alternative action, goods, services or money.

DeMartino points to this case as just one exemplifying the faulty operations of moral geometry.

“The question is, are there some harms that compound over time that don’t dissipate? If there are such harms as a consequence of what Congress does, then we can’t use strategies like short-term adjustment costs to dismiss the harms because, in fact, the harms don’t go away — it’s nothing short-term. They become a long-term feature of our society.”

After explaining the idea of economic and compounding harm, DeMartino also pointed to cascading harm: when one kind of harm sets off others.

“Economic harm can generate physical harm in the form of increased morbidity or premature mortality, or … a reduction in education. That’s a harm you might think of as an autonomy harm. It also leads to diminished income, it leads to increased economic insecurity, it can lead to a whole range of other harm.”

While the issues brought up in DeMartino’s book and presentation are gaining more traction within the economic community, some within the audience questioned whether the professor’s ideas needed further research to be fully understood and accessible for implementation, as well as the implications of the elimination of harm.

Katherine Zuily ’25 wished that “DeMartino elaborated on what his ideas would look like in practice. I think it is difficult to establish what harm means in economics because it is far more arbitrary than what harm looks like within other fields he mentioned, such as medicine. I wish that DeMartino spoke more about how decisions could be made by governments using his framework.”

Zuliy also noted that economic departments within institutions such as MHC have limitations in regard to implementing issues of ethics as mentioned by DeMartino into their curriculums: “I don't think that it is possible for them to establish a course about this subject given that the field doesn't really exist,” she said.

DeMartino however, acknowledges that “economic harm can never be eliminated.” “It’s a tragedy … It’s something that has to be managed. You can’t get rid of it. You have to manage it,” he said, maintaining that this is the focus of his study and his proposal of de-influence.

“Critique doesn’t come from the left or the right,” DeMartino said. “Instead, … It’s a request to the profession.”

Overall, these types of conversations are valuable to be had, and Zuliy acknowledges that “there should be more events like this because they help students to think more deeply about topics discussed in class and think about how ideas can be applied in real-life situations.”