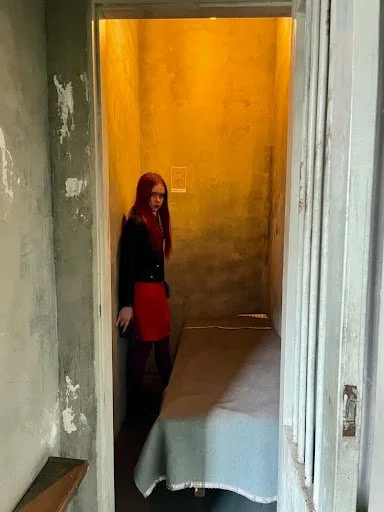

Photo courtesy of Steve Goodman

Anna Goodman in a former Portuguese prison.

By Anna Cocca Goodman ’28

Staff Writer

“You know,” my father said, “Portugal is supposed to be sunny.”

But instead, it’s 2 p.m. on a rainy Sunday in January 2024, and I’m tumbling into a museum whose entrance is tucked into a Lisbon street corner, with soaking wet hair, rudimentary (at best) Portuguese, and an umbrella broken in ways I didn’t know umbrellas could break.

To be honest with you, I agree to go inside partly just to get dry.

But once there, ticket in hand, I find myself faced with a deep red wall, painted with the words: sem memória, não há futuro. I ask the first person I see to explain. “It means,” the woman replies, “without memory, there is no future.”

When someone says “fascism,” what do you picture?

I asked three Mount Holyoke College history professors who specialize in different time periods and continents to see what they thought.

“In Ghana, around the …'70s and the '80s, there were several revolutions and what a lot of people may consider authoritarian rule,” Professor of Pre-Colonial African History Ishmael Annang said.

“I mean, there's a lot of oligarchies in history,” Professor of Modern African American History, Caleb Smith replied. “But if you're talking about a dictatorship, I mean, Putin … that's as good an example as there gets.”

“Especially as a Jewish studies professor,” Yiddish Book Center Director and Professor Madeleine Cohen said, “when I think of fascism, of course, I tend to think of Nazi Germany.”

Whatever you think of, I don’t think it’s Portugal.

So let me change that.

The story of Portuguese dictatorship officially begins with a military coup in 1926, when António Salazar came to power; a man, who, according to the Huxley Almanac, was “a rather strange dictator … Despite being an autocrat, he didn’t build any palaces for himself, nor did he wage any wars … [but] he remained at the top for 36 years, becoming the longest-ruling dictator in Europe.”

Salazar’s reign of terror was marked not only with extreme violence but with a widespread suppression campaign which was nicknamed “Lápis Azul,” or “blue pencil,” after the tools his censors used to strike out content deemed unsuitable for publication.

In 1936, after drafting a new “constitution,” Salazar made a speech whose most famous lines were as follows: “We do not discuss the fatherland and its history. We do not discuss the family and its morals. We do not discuss the glory of work and its duty. We do not discuss authority and its prestige. And we do not discuss God and his virtue.”

“It sounds like a really good, almost textbook example of dictatorship,” Cohen said, later in our interview, “So what it makes me think of is, why in the U.S. do we only talk about Hitler?”

And it isn’t just the U.S. either. The Museu do Aljube, the museum I mentioned at the beginning, says in their mission statement, “[We] intend to [take] on the struggle against the exonerating, and, so often, complicit amnesia of the dictatorship we faced between 1926 and 1974.”

The museum itself is actually located in a building that was once used to imprison and torture political dissidents, and it is a hauntingly immersive experience. There are the sudden flashes of camera light. There are the cell bars criss-crossing the ceilings. There are the telephones that ring through the loudspeakers, making your heart race out of your chest before you can remind yourself that you haven’t done anything wrong.

But the most affecting part is a dark, silent space, a seven foot by four foot room, kept pristine from its days as an isolation cell. Inside, there’s just enough room next to the wooden pallet and flea-bitten blanket masquerading as a bed for seventeen-year old me to walk up to the opposite wall and see, scratched with some kind of sharp rock, 12 tally marks and the words: “João, 1940.”

It is an image that will never leave my mind. And, really, that’s the point.

“Sem memória, não há futuro,” or, as the stranger I met kindly translated, “without memory, there is not a future,” is a quote all over the museum. Its mission statement, as it says on its website, is “[to preserve] the memory of histories and active citizenship, and [to break] the silence in which everyone was submerged and rescue them in order to educate the younger generations.”

But who are those younger generations? Who are these people that the museum is fighting for?

I’ll tell you.

It's the Angolan teenager in the cafe who showed me a video of him playing fútbol with his team and said with a wink, “Promise you’ll look for me on the TV one day.” Fifty years ago, they wouldn’t have let him play.

It's the German waiter who bartends part-time for fun, and, in between spouting cheesy pick-up lines and unserious marriage proposals, tells me about his gay brother and what he said when he came out to him. (“The way I see it, if everyone only liked rice, nobody would buy pasta. And then all of Italy would be out of business. You need variety!”) Fifty years ago, he would have been arrested.

It's the Korean exchange student in the Museu do Aljube, who managed to teach me the little phrase in Portuguese that made this article come to life with her own alphabet. (“No-no, ha, ha, like laughing in Hangul.” Ah! Jaraesseoyo!). Fifty years ago, she wouldn’t even have been there, and she definitely wouldn't have been allowed to study journalism.

It’s the seventeen year-old American girl who complains when her father drags her to some museum because he remembers when he was her age and hearing about a revolution half a world away, not knowing that she’ll be just as moved by the story as he was in real time. She’s also a reporter. But she hasn’t written this story yet.

And it’s you too.

Because knowledge, protest, dissent – it isn't just important for those at the highest level. From the dissidents imprisoned in claustrophobic isolation cells to the journalists who printed their calls to action in secret, to the people marching in the streets, to everyone who had the strength to keep living anyway, their actions matter.

After thanking each of my interviewees for their time, I asked if I could read a short quote from a poem by Manuel Allegre, drawn on the museum’s walls. “Mêsmo na noite mais triste, em tempo de servidão, há sempre alguém que resiste, há sempre alguém, que diz: não.” Even on the saddest night in times of servitude, there is always someone who resists, there is always someone who says: no.

“It is so true,” Annang said. “I think society has created the false notion that those who do not get on the streets or those who do not gather on the field are probably not in some form of dissent or resistance. But just saying no is resistance.”

It’s 2 p.m. on a sunny Wednesday in May 1974, and a waitress is walking home from work. When she passes a young soldier, she hands him a carnation, which he puts in the barrel of his rifle. Within hours, every soldier has a red flower in his gun, and thus, because of Celeste Caeiro, the day the Portuguese dictatorship crumbled is known as the Carnation Revolution.

And I would be lying if I said all this and didn’t tell you that, in writing this article, I was a little scared. I’m still scared. Just a little over a week ago, ABC was intimidated by the White House into pulling Jimmy Kimmel’s show from the air after he even dared to insinuate that President Donald Trump was not as broken up about Charlie Kirk’s death as he claimed. I’m eighteen now, and we are watching a fast-paced descent into fascism in real time in our own country.

But I’ve seen change happen with my own eyes, from the women’s marches in 2016 to the Black Lives Matter movement in 2020, and, on a smaller scale, on campus, with the protests over fair wages for our staff.

Change wasn’t just made by the members of the Mount Holyoke workers’ unions striking, but by the students who marched with them, by the choir who turned their backs during Commencement, by the speakers who took pains to show their support, by the people who painted signs even if they couldn’t walk, by the photographers who documented the protests and by the journalists here at MHN who wrote so beautifully about them.

“The museum is what taught me that you can do something small,” I said to Smith during our interview. “I'm kind of curious what you think, say, an average person could do?”

“I would challenge the word ‘small,’” Smith answered. “I would use everyday acts of resistance. Truth is, no act of resistance is small ... And so that has been something [constant] throughout, especially looking at the American Civil Rights Movement [in the] African American context. Everyday resistance has always been a thing. And collective organizing, whether it is pickets, boycotts, or even, putting on stage shows. It all counts.”

“I think that there is so much that students can do,” Annang said. “You have the ability to educate yourself and educate your peers so that when we have people protesting, it's not just because they're following the crowd, but they really know and have a conviction of what exactly they are protesting about.”

Sem memória, não há futuro. Without history, there is no future. Without history, there is no us. And without us, there is no history.

Quill Nishi-Leonard ’27 contributed fact checking.