Photo by Kannille Washington ’28

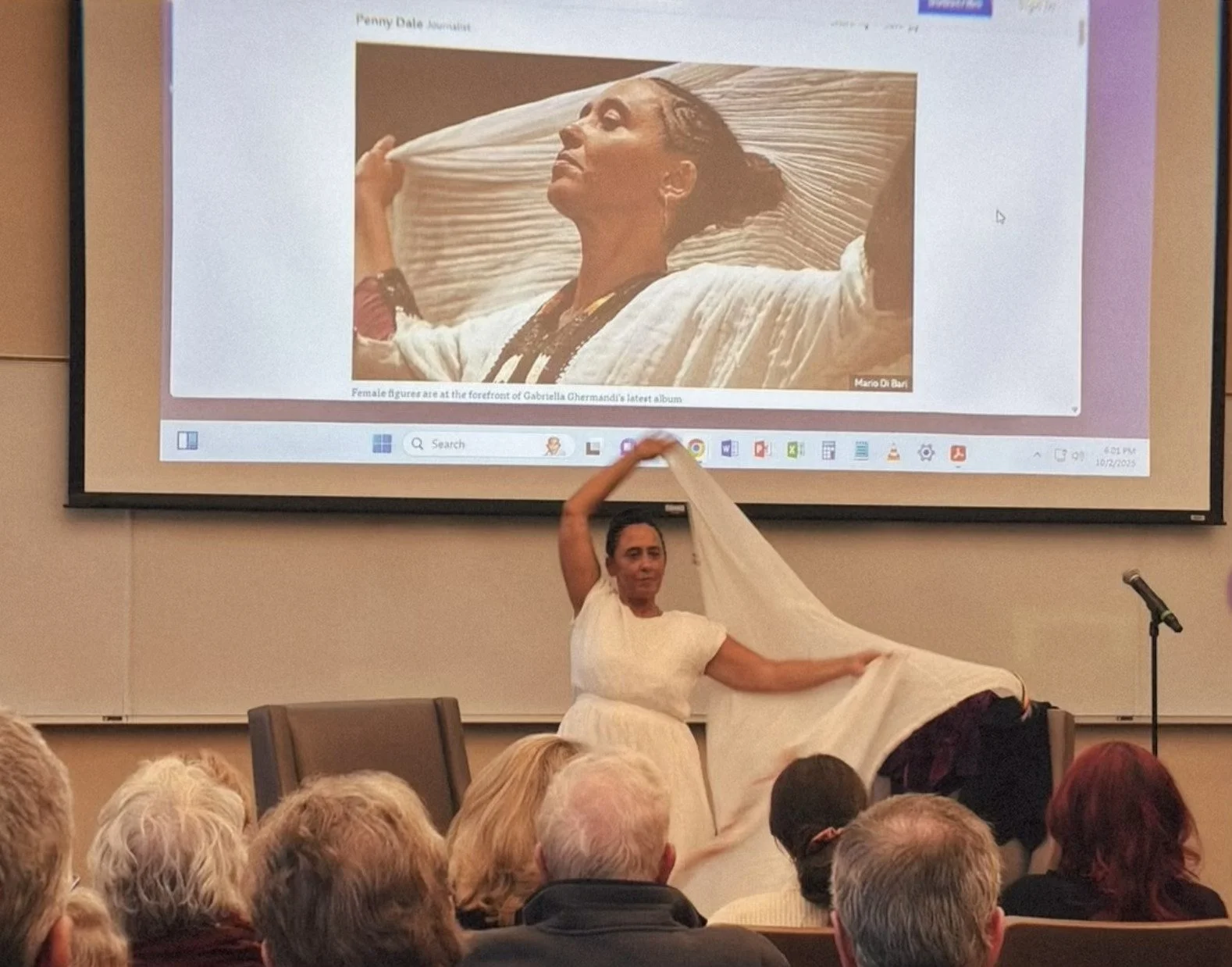

Photgraph of Gabriella Ghermandi’s lecture and performance on “Queen of Flowers and Pearls.”

By Kannille Washington ’28

Staff Writer

“I must make peace with my land.” Gabriella Ghermandi echoes the words of her mother as they moved from Italy back to Ethiopia.

On Oct. 2, in Dwight Hall, Gabriella Ghermandi gave a lecture and performance on her novel, “Queen of Flowers and Pearls.” The annual Giamatti Lecture is given through the Italian department in honor of Mount Holyoke’s Valentine Giamatti, who was an Italian professor at the College in the 1940s.

This year, Gabriella Ghermandi came to speak about her book, which has become a classic in Italian literature. Ghermandi shared insights on the Italian occupation of Ethiopia and the reasons why storytelling and oral history are important in preserving cultural heritage in the face of colonization.

“I grew up in Ethiopia, and I attended the Italian school. And it was a very racist environment, very fascist,” Ghermandi said in an interview with Mount Holyoke News the day before the lecture.

In her lecture, she began by addressing how people and history disregard Italy’s colonialism. Compared to the reach of other countries such as France and Spain, Italy is least often held accountable for the harm they have caused to the Ethiopian community during their occupation from the 1930s to the 1940s, and its lasting impact.

Despite this occupation and, additionally, mass levels of immigration in Italy, there is little acknowledgment of the racial diversity in the country.

“It’s a very old issue that belongs to fascism and even before. Just trying to maintain the purity of the Italian blood, which belongs to the Roman Empire,” Ghermandi said.

Ghermandi, eloquently, introduced her novel as personal, but not autobiographical. She presented the idea that there is still a “bleeding wound” in her maternal history.

“Regina di fiori e di perle” — which translates to “Queen of Flowers and Pearls” — is the story of a young girl who finds value in storytelling and oral history while retracing the centuries of history in her Ethiopian heritage. Ghermandi said, “I always had my eyes fixed on the Italian community because I felt threatened, but I never turned to the other one, which was the Ethiopian one, which was the one that actually supported me.” This late connection to her heritage led to her decision to write the novel.

The Italian occupation was organized in such a way so as to control the movement of Ethiopian pathways, people and cultures. This control extended to Ghermandi and her mother’s own perceptions of their identities.

In her lecture, Ghermandi told the story of her mother’s childhood. She shared that her mother was taught a game in which kids would run away from the “Black man.” Eventually, Ghermandi’s mother taught her the same game: To run away from anything Black. As she grew older, this was how she went about life, trying to run away from anything Black about herself. “But my body, heart and soul are rooted in Ethiopia,” Ghermandi came to realize.

Through music, Ghermandi shared her culture and traditions. She speaks on the sounds that made up her childhood in Ethiopia, as well as other artists she admires that have distinct ways of braiding culture and tradition into their music. Pathways open, free to move in her identity, her voice filled the room with passion and an unmistakably playful nature. There is an assuredness to her culture and to her passion.

But for her mother, there is still something to find. Italy is not the land of superiority, which Ghermandi’s mother realized once she spent time in Bologna. “I want to make peace with my land,” Ghermandi recounts her mother saying.

So Ghermandi and her mother traveled back to Ethiopia in search of their family, a long line of strong women.

As the lecture came to a close, Ghermandi highlighted Shawaragad Gadle, Kebedech Seyoum and Senedu Gebru to reinforce the legacy and impact of Ethiopian women. Very poignantly, she stated, “I feel very proud of being Ethiopian.”

Alayna Khan ’28 contributed fact-checking.