Courtesy of WikiCommons

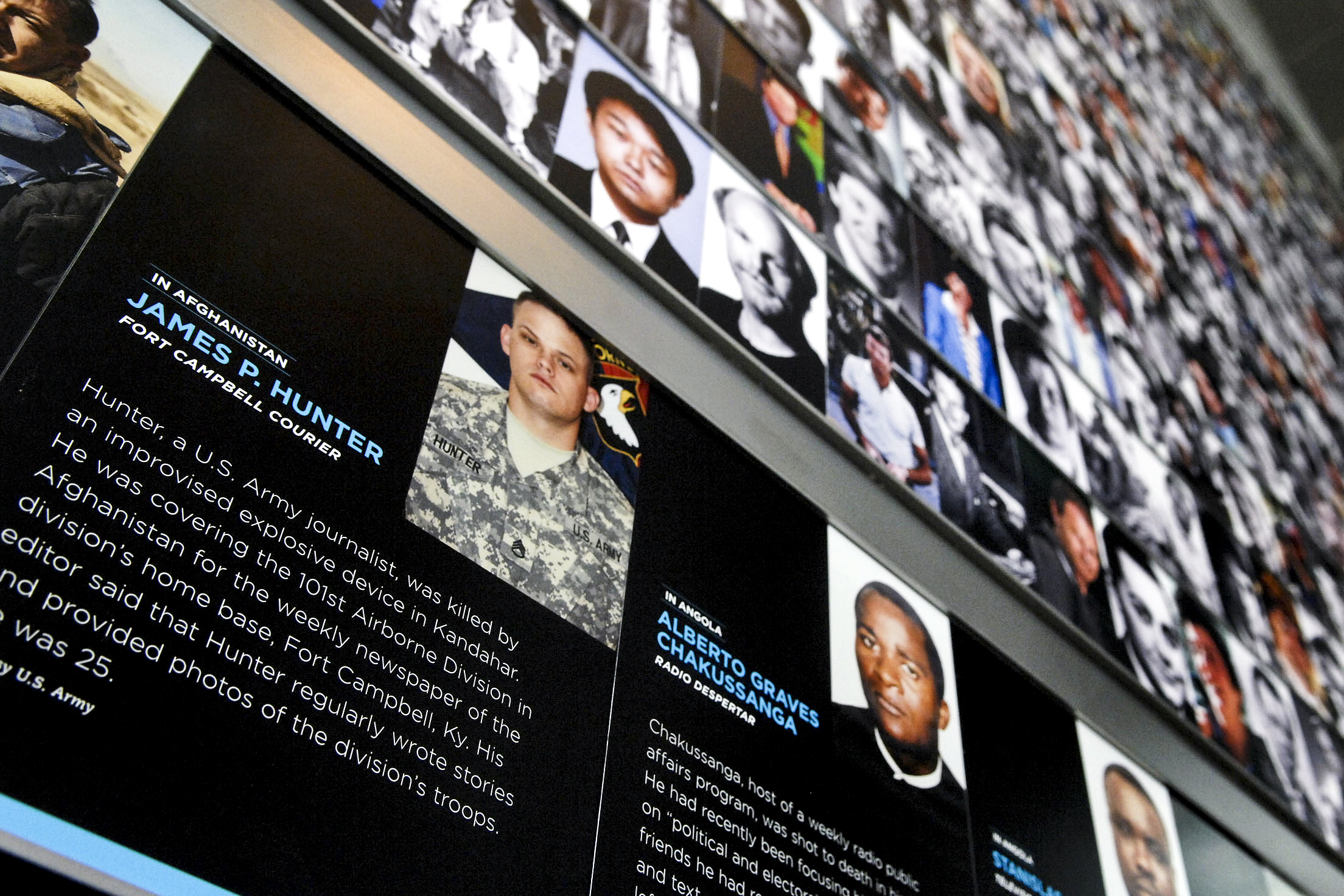

The memorial for fallen journalists at the Newseum in Washington D.C.

BY CASEY ROEPKE ’21

The disappearance of Jamal Khashoggi, a prominent Saudi journalist, is the latest addition to a recent international upsurge in violence against reporters. Khashoggi was the former editor-in-chief of Al-Watan, where he covered stories ranging from critiques of Saudi government figures to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. In 2017, he began a self-imposed exile in the U.S., during which he wrote a column for the Washington Post.

On Oct. 2, 2018, Khashoggi went to the Saudi Arabian consulate in Istanbul to pick up some documents. He has not been seen since. According to the BBC, Turkish officials have stated that they have audio and video evidence of Khashoggi, who they claim was “tortured and killed on the premises by a team of Saudi agents.” Another source, an anonymous senior Turkish official, told the New York Times that Khashoggi was killed within two hours of his arrival to the consulate and then dismembered.

Khashoggi’s story, although horrifying, is not unique. According to Pete Muller, a visiting lecturer of International Relations at Mount Holyoke and former multimedia reporter specializing in conflict, “[While] investigating something about conflict, if you’re not afraid, the chances are you’re not reporting anything of significance.”

In many cases, journalists are putting themselves in danger to uncover the truth, yet the stakes seem to be raising — in 2018, journalists have been murdered at a higher rate than in 2017. In 2017, 50 journalists were killed, making it “the least deadly year for professional journalists in 14 years,” according to Reporters Without Borders, an international nonprofit focusing on issues regarding freedom of the press. However, this trend has not continued; the first nine months of 2018 have been deadlier for journalists than the entirety of 2017. As of Oct. 1, Reporters Without Borders identified 56 journalists “whose deaths were clearly linked to their work.”

Journalism is an industry that depends on access to information the general public is not privy to, as well as security in reporting. With the rise of right-wing populist politicians like President Trump in the U.S., who dismiss news media as “the enemy of the people,” the industry has become increasingly dangerous. Todd Brewster, a visiting senior lecturer in English at the College and former producer for ABC News, said that “in an era when authoritarianism is on the rise, it only follows that we would see more journalists targeted for abuse. Authoritarians don’t like the accountability that journalists demand of those in power.”

The advocacy director for the Committee to Protect Journalists, Courtney Radsch, noted the significance of journalists’ deaths in today’s polarized political society. “There is an increase in attacks on journalists and journalism as an institution that is important to democracy and to the foundation of human rights,” she said. “And we see that this is being undermined around the world.” The New York Times reported that although “anti-press rhetoric has not been directly linked to the rising incidence of murders of journalists,” this attitude creates a social climate that endangers the careers and lives of reporters.

According to the New York Times, outside of conflict zones like Iraq and Syria, Mexico is the deadliest country for journalists. In the Committee to Protect Journalists’ annual compilation of fatalities, the committee recorded at least six murders of reporters in Mexico alone during 2017. Cecilio Pineda Birto, a freelance reporter, was shot on March 2, 2017. Also in 2017, Javier Valdez Cárdenas was shot 12 times outside of the investigative weekly newspaper that he founded. Miroslava Breach Velducea, a correspondent for La Jornada, was shot eight times in front of her child and died on March 23, 2017.

Europe is also a hub for violence against journalists. In Bulgaria on Oct. 6, Viktoria Marinova, the host of a news show known for anti-corruption ideology, was discovered in a city park, raped and beaten to death. Although Bulgarian officials denied any connection between the murder and Marinova’s work, her colleagues are pointing to this incident as an example of the larger trend of threatening journalists with violence to silence a story. Reporters Without Borders has called for a formal investigation.

The killing of journalists inspires fear in remaining media personnel, but it also effectively silences journalists in the process of discovering deeper truths. Jan Kuciak (who formerly worked to break the story of the Panama Papers) was investigating the links between ‘Ndrangheta, an Italian organized crime group, and the Slovakian government before he and his fiancée were shot to death.

Not only are journalists being killed in large numbers, they are also often silenced with forced disappearances or arrests. On Oct. 10, 2018, the Committee to Protect Journalists called on Myanmar to release three journalists who were arrested for causing “fear or alarm,” as reported by Reuters. In Kazakhstan, police detained a French journalist and banned him from filming. And in Somalia, authorities held Mohamed Abdiwali Tohow, a broadcast journalist, for spreading what they determined to be “false news.”

According to Muller, freelance journalists, like Galizia, are particularly vulnerable to threats or actual violence because they don’t have the protection of a news agency. “If you’re a staff reporter or staff photographer it gives you a degree of confidence that [as an] employee, [the publication] will be there for you with the full breadth of their resources,” he said.

Muller has been in situations where he was threatened for getting too close to discovering information. “It’s very scary to have powerful people threaten you,” he said, reflecting on situations where he stopped his reporting after confrontations with powerful people intent on stopping a story. “When you find yourself in a position where the authorities are the ones threatening [you], it’s really unsettling… I was relatively young as a journalist and I was a freelancer, I didn’t feel that I knew what I was doing enough to carry on.”

While those in the U.S. are used to viewing freedom of the press as a tenet of democracy — by some, news media is even considered to be the fourth constitutional check on governmental power — it’s a different story around the world. Journalists are being silenced, threatened and killed to prevent the public from seeing their stories, which could be disruptive to the structure of government or personal reputations.